Victorians value behaving with honesty and integrity.

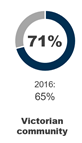

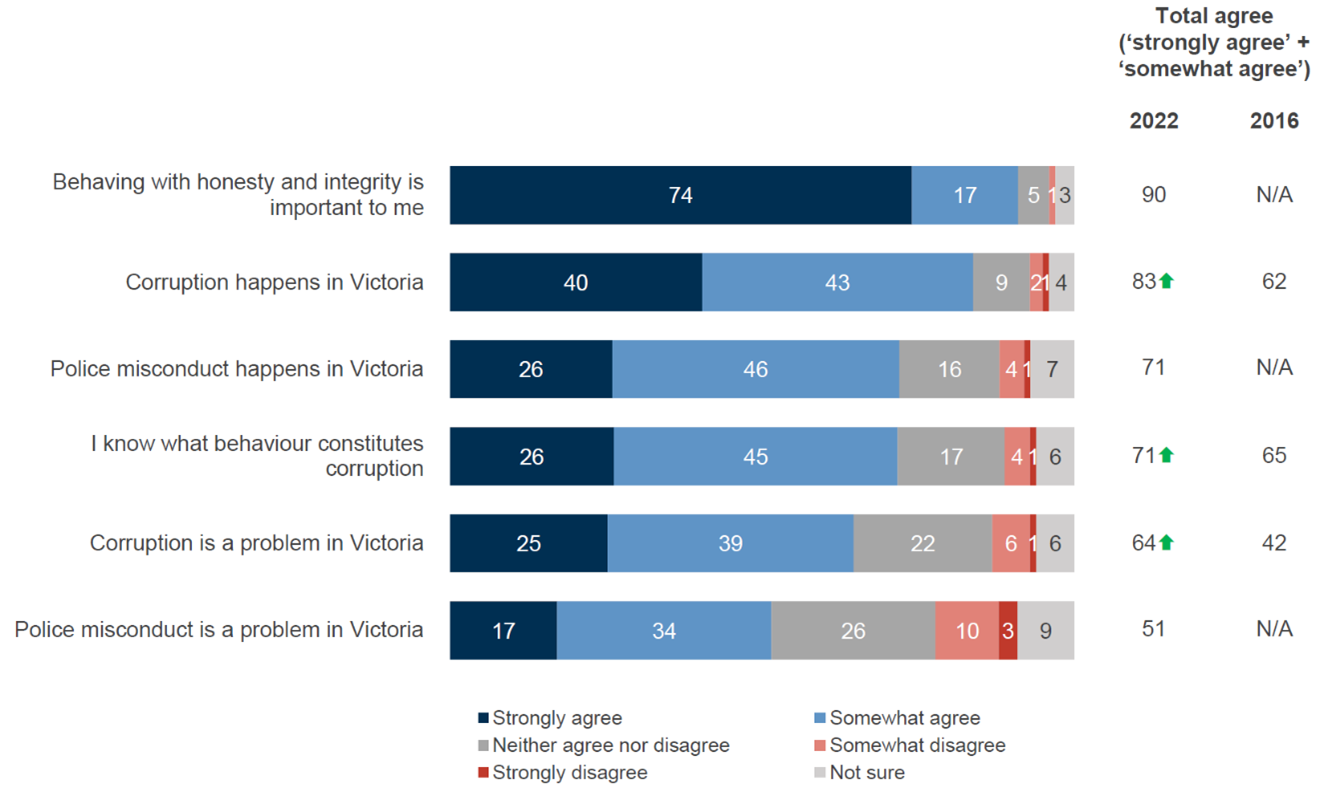

Most Victorians (90%) agree that ‘behaving with honesty and integrity is important to me’ and 71 per cent agree that they know what behaviour constitutes corruption. The proportion who know what behaviour constitutes corruption has increased significantly compared to 2016 (65%).

Most Victorians (90%) agree that ‘behaving with honesty and integrity is important to me’ and 71 per cent agree that they know what behaviour constitutes corruption. The proportion who know what behaviour constitutes corruption has increased significantly compared to 2016 (65%).

An increasing proportion of Victorians agree that corruption happens in Victoria.

Most Victorians (83%) believe corruption happens in Victoria and 64 per cent think it is a problem. Significantly more Victorians believe it to be a problem in 2022 compared to 2016 (42%). People living in regional locations are significantly more likely to think corruption happens in Victoria (88%).

By comparison, seven in 10 Victorians (71%) agree police misconduct happens in Victoria. People who identify as LGBTIQ+ are significantly more likely to agree police misconduct happens in Victoria (77%) and people who speak a language other than English are significantly less likely to agree it happens (65%).

There is understanding of government behaviours that constitute corruption or misconduct.

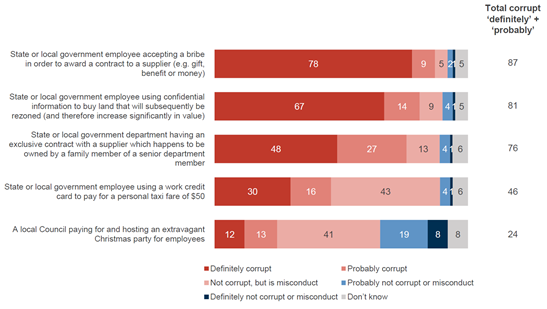

There is wide agreement that a range of actions by state or local government employees are corruption. A little over three quarters (78%) claim that a public servant accepting a bribe to award a contract is ‘definitely corrupt’ behaviour. Two thirds (67%) claim that using confidential information to buy land that will be rezoned is ‘definitely corrupt’. Use of a work credit card for a taxi fare or a council holding an extravagant Christmas party are less likely to be viewed as corruption and more likely to be viewed as misconduct.

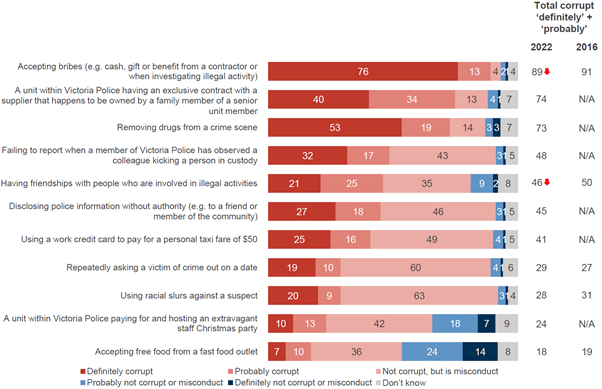

There is broad agreement on police behaviours that are viewed as corruption or misconduct.

Nearly all police behaviours evaluated are viewed as either corrupt or misconduct by a large majority of Victorians (around nine in 10), however the lines appear blurrier in understanding what constitutes corruption or misconduct in Victoria Police. Bribes or removing drugs from a crime scene are clearly understood to be corruption (76% and 53% respectively understand this to be ‘definitely corrupt’). However, many behaviours are considered misconduct rather than corruption, such as repeatedly asking a victim out on a date (60% consider this to be misconduct) or using racial slurs against a suspect (63%). An extravagant staff Christmas party and free fast food are least likely to be considered either corruption or misconduct.