|

Terms |

Explanation/Expanded abbreviation |

|---|---|

|

Confidential information |

As per the definition given in section 125 of the Local Government Act 2020 |

|

CMS |

Case Management System |

|

CEO |

Chief Executive Officer |

|

Councillor |

The Local Government Act 2020 defines a councillor as a person who holds the office of member of a Council. Councillors are democratically elected by the residents and ratepayers of the municipality, and are responsible for representing the local community, reviewing matters and debating issues before their council. |

|

LGI |

Local Government Inspectorate |

|

Local government |

The term local government refers to the 79 councils in Victoria along with their employees, contractors and councillors. |

|

Local government employees |

Unless stated otherwise, local government employees include contracts, casual and ongoing employees. |

|

IPP |

Information Privacy Principles |

|

IT |

Information Technology |

|

MoU |

Memorandum of Understanding |

|

OVIC |

Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner |

|

Official information |

Any information (including personal information) obtained, generated, received or held by or for a Victorian public sector organisation for an official purpose or supporting official activities. This includes both hard and soft-copy information, regardless of media or format. |

|

PDP |

Privacy and Data Protection |

|

PROV |

Public Records Office Victoria |

|

VAGO |

Victorian Auditor-General’s Office |

|

VO |

Victorian Ombudsman |

|

VPDSF |

Victorian Protective Data Security Framework |

|

VPDSS |

Victorian Protective Data Security Standards |

|

VPS |

Victorian Public Service |

Research reports

Unauthorised access and disclosure of information held by local government

An overview of key risks associated with unauthorised access and disclosure of information held by the local government sector, this report explores the drivers of these risks, as well as potential prevention, reporting and detection measures.

Local government manages a wide range of official and confidential information relating to citizens, planning and development, economic and financial analysis. This information assists councils to lead and govern the local community and informs council decisions. Information should be secured and handled in line with best practices outlined and referenced in this report. Information that is lost, stolen or accessed by unauthorised persons impacts community and individual safety, and has significant flow-on costs for the community and their local government.

This report discusses how the misuse of information or material by both local government employees and councillors, acquired in the course of the performance of their duties, may constitute corrupt conduct. It also covers potential prevention, reporting and detection measures.

Focusing on local government, this is the final in a series of three reports outlining the key risks of unauthorised access and disclosure of information within the Victorian public sector.

HTML version of report

-

-

Local government manages a wide range of official and confidential information relating to citizens, planning and development, economic and financial analysis. This information assists councils to lead and govern the local community and informs council decisions. Information should be secured and handled in line with best practices outlined and referenced in this report. Information that is lost, stolen or accessed by unauthorised persons impacts community and individual safety, and has significant flow-on costs for the community and their local government.

This report provides an overview of key risks associated with unauthorised access and disclosure of information held by the local government sector. It explores the drivers of these risks, as well as potential prevention, reporting and detection measures.

Focusing on local government, this is the final in a series of three reports outlining the key risks of unauthorised access and disclosure of information within the Victorian public sector. The previous two reports focus on Victoria Police and state government bodies respectively.

The responsibilities and functions of local government employees and councillors are significantly different, both in everyday activities and under legislation. Local government employees are responsible for the administration of local government while councillors are the elected representatives.

IBAC acknowledges that while there are shared corruption risks across both parts of local government, the drivers of these risks for councillors are often markedly different due to the elected nature of their role. IBAC’s separate analysis of the drivers of unauthorised access and disclosure by councillors is in section 4.

This report discusses how the misuse of information or material by both local government employees and councillors, acquired in the course of the performance of their duties, may constitute corrupt conduct.

IBAC’s role includes informing the public sector and the community about the risks and impacts of corruption and ways it can be prevented.

IBAC’s intelligence and research reports assist public sector agencies to help identify corruption, and to expose and prevent it. For the purposes of this report, the public sector includes local government.1

This report was informed by an analysis of

IBAC findings from investigations and research, consultation with interstate and Commonwealth integrity bodies, the local government sector, and key agencies responsible for information management, privacy and data protection in Victoria.

The unauthorised access and disclosure of information is a consistent theme in investigations of corruption across Australia. IBAC’s previous strategic assessments and public reports identified that it remains a key issue for Victorian public sector agencies holding security-classified or sensitive information such as Corrections Victoria2 and Victoria Police.3

Due to the access that police, custody and correctional officers have to official information and law enforcement data, it is unsurprising that a large proportion of investigations and assessments by IBAC and partner agencies often focus on these sectors.

Although these agencies face heightened risks, unauthorised information access and disclosure is a risk across the entire Victorian public sector. It is especially so for employees with high levels of access to official information, such as system administrators or IT specialists. In light of this, IBAC has undertaken an analysis across its jurisdiction to ascertain risks faced by different sectors and levels of government.

The increased reliance upon technology for work and personal use has improved efficiency but has also raised the risk of public sector employees easily copying or replicating data for circulation. While technology has benefited the work of the public sector overall, it has made it ‘very easy to disclose information – in terms of time, quantity and sensitivity – and difficult, if not impossible, to retrieve it’ 4 once disclosed. However, technological footprints of unauthorised disclosures can make it easier for agencies to substantiate allegations once they have conducted their investigation.

The wide range of information managed by local government includes the personal and business details of ratepayers as well as the planning and business information of council. A breach of the security of this information can risk residents’ privacy, enable corruption and compromise the democratic and fair functioning of local government.

-

- IBAC intelligence suggests information misuse by employees is underreported across local government, as well as the public sector more broadly. This may be due to misuse being under-detected, an underappreciation for information security and privacy rights of citizens, or a lack of awareness that information misuse and disclosure may constitute an offence in itself.

- Integrity agencies are more likely to receive allegations of information misuse by councillors than by other employees. The Local Government Inspectorate (LGI) reports approximately one-third of the complaints it receives relate to information misuse, with the majority of these being against councillors. One reason these allegations are more common is that other councillors may be motivated to report councillors they oppose.

- The detection of information misuse often does not occur until investigations have started for other misconduct or corruption. This is partly due to systems which have not been fully developed, as well as a lack of processes to either detect unauthorised information access in isolation or flag that it has occurred. An exception to this is investigations undertaken by the LGI into disclosure of confidential information under section 125 of the Local Government Act 2020.

- Sharing information with approved third-parties also presents corruption risks, partly driven by confusion created by the complex legislative, administrative and regulatory environment governing information sharing. Although policies may be in place to control information access and disclosure by third parties, it is difficult for agencies owning the information to proactively detect and enforce information misuse.

- The unauthorised access and disclosure of information is a key enabler of other corrupt behaviour but is often rated as low risk by agencies. This is evident in lower than expected numbers of reports to IBAC, and in behaviours uncovered in investigations undertaken by IBAC and other public sector agencies. Improved understanding of information misuse as an enabler of corruption will help local government detect and investigate such incidents.

- Unauthorised disclosures to the media is a risk across local government and to public sector agencies more broadly. IBAC believes these incidents are difficult to substantiate due to the source of information leaks often being difficult to identify.

- Unauthorised information access and disclosure is a key corruption risk in procurement and planning. This can be mitigated with improved awareness of risks and by implementing best procurement practices.

- Increased use of personal devices and smartphones in the workplace has made unauthorised disclosure of information much easier. The level of maturity in how the local government sector deals with this increased risk is extremely varied.

- Customised auditing of information access is underutilised and its benefits are underappreciated across the Victorian public sector, including local government. A program of proactive, extensive and repeated auditing could more effectively identify and deter unauthorised access of information.

- The Victorian Protective Data Security Standards (VPDSS) were introduced in 2016 and updated in 2019. The VPDSS and the Victorian Protective Data Security Framework (VPDSF) are both established under Part 4 of the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 (PDP Act) which explicitly excludes Councils, however, it is common for them to act as, or perform the functions of, a public entity. Given these arrangements, most councils will oversee and administer the information security obligations of these entities and their data. The VPDSS establish 12 high-level requirements to protect public sector information. Although Councils are not expressly bound by the VPDSS, if they apply the principles within the VPDSS it can reduce unauthorised information access and disclosure. The impact of the VPDSS on longer term cultural change depends on how successful local government is in implementing the VPDSS and aligning their practices.

-

Scope

This report considers corruption risks related to information misuse by local government, its employees, and councillors.

This report does not consider unintentional misuse of information as this is unlikely to engage IBAC's jurisdiction and amount to corrupt conduct.

Under the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission Act 2012 (the IBAC Act), IBAC may investigate and take complaints about corruption across the public sector, local government, police, parliament, and the judiciary in Victoria.

IS UNAUTHORISED ACCESS AND DISCLOSURE OF INFORMATION AND DATA CORRUPT?

The IBAC Act defines corrupt conduct (among other things) as conduct of a public officer that involves the misuse of information or material acquired in the course of the performance of their functions, being conduct that would constitute a ‘relevant offence’. 5

Unauthorised access and disclosure of information by employees of public sector agencies can be considered corrupt conduct under the above IBAC Act definition of corrupt conduct depending on the circumstances of the access or disclosure.

CAN YOU MAKE AN UNAUTHORISED DISCLOSURE OF INFORMATION WHEN REPORTING SUSPECTED CORRUPTION TO IBAC?

Employees and councillors can make disclosures of information without the permission of their employer in the following circumstances.

Under the Public Interest Disclosure Act 2012, a person may make information disclosures to IBAC, an investigating entity or the public body in question about employees of that entity if the information shows or tends to show the subject officer is engaging, has engaged, or is proposing to engage in improper conduct or detrimental action.6

The Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner (OVIC) defines information management as the way in which an organisation plans, identifies, creates, receives, collects, organises, governs, secures, uses, controls, disseminates, exchanges, maintains, preserves and disposes of its information.7

Good information management promotes good information security and assists in deterring unauthorised access and disclosure of official information. This report also looks to other stages of the information management cycle where it is relevant to unauthorised access and disclosure of information held by the local government sector in Victoria.

This report provides analysis of information misuse by local government within Victoria and excludes information misuse outside of IBAC’s jurisdiction unless providing context for analysis.

This report acknowledges that employees and councillors are allowed to disclose information without permission in certain circumstances, particularly when wishing to report police misconduct or corrupt conduct to IBAC, Victoria Police or another investigating entity. These types of disclosures (sometimes referred to as whistleblowing disclosures) are assessable for protections under the Public Interest Disclosure Act 2012.

Terminology

The local government sector in Victoria includes 79 local councils and their employees, contractors and councillors. The term, local government, is used to refer to the sector, and where relevant, local council or council is used to refer to an individual council.

IBAC receives complaints from the public and notifications from public sector agencies. A complaint or notification may include multiple allegations, all of which are individually assessed. This report includes summaries of allegations received by IBAC as a means to illustrate key points.

IBAC notes there are limitations with the use of these examples, including:

- allegations are unsubstantiated at the time of receipt

- allegations can be incomplete, lack detail, from an anonymous source, or may not individually name the subject of the allegation

- allegation data is not a comprehensive or reliable indicator of the actual prevalence of particular activities, or the risk mitigation practices and compliance activities already in place.

Despite these limitations, analysis of allegations can help identify trends or patterns and provide practical examples of trends.

This report refers to a number of terms defined in the PDP Act, including ‘personal information’, ‘sensitive information’, and ‘law enforcement data’. For clarity, these terms are used within the report in their ordinary sense, unless otherwise stated. The term ‘confidential information’ is a defined term in the Local Government Act 2020 and its use in this report reflects that definition.

This report often refers to unauthorised access and disclosure of information as ‘misuse of information’.

Context

The unauthorised access or disclosure of information held by local government can have serious adverse consequences. It can threaten community safety, increase the costs of council-funded projects and contracts, reduce the amount of money available for much needed public services, and make people reluctant to share information with their local government.

Accountability, trust and transparency in how local government protects and manages information, in particular official information, is essential for good governance and for councils to work effectively. Any incident or series of incidents which undermine the public’s confidence in local government’s ability to secure official information is likely to affect the willingness of the public to provide information that assists local government in performing its functions.

A strong reputation is fundamental to the success of an organisation. A 2019 survey of leaders’ attitudes found that integrity, quality of products and services, relationships and culture are the four most important drivers of an organisation’s reputation. Notably, it found that a good culture had a positive effect on staff morale, innovation, operational efficiencies and a sustainable business with long-term value. For local councils, these findings show that integrity and culture are connected, and these can directly impact the community and the services that councils deliver.8

Information misuse can have negative financial consequences for local government, which can then impact the services available to the community. This information misuse might include information leaks to suppliers during procurement, leading to less competition in future procurement processes. In an IBAC survey of Victorian suppliers to state and local government, approximately one-third of respondents stated they were discouraged from tendering for work because of concerns about corruption.9 This may be influenced by perceptions the tender has been won due to corrupt processes.

Local government holds official information on clients of council services, planning and business information, as well as personal information of community members. Any unauthorised access and disclosure of this information can impact the efficiency of local government in providing services as well as the safety and wellbeing of citizens.

Local government has a responsibility to ensure this information is protected from misuse, by both employees, councillors and outsiders seeking to gain access to official information.

Local government is a unique sector with employees managing the administrative and business side of local councils, and councillors making decisions as elected representatives of their communities. As such, the corruption risks and drivers for these groups can differ and should be considered separately by councils.

Information misuse can assist organised crime and encourage further offending. The Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission has highlighted public sector corruption, including information misuse, as a key enabler for organised crime.10 IBAC has previously explored the issue of public sector employees providing information to organised crime entities.11 Information leaks by public sector employees, including any from local government, to organised crime groups is serious and warrants ongoing scrutiny, including continual auditing, training, and guidance for employees.

IBAC’s investigations have consistently identified information misuse as a key element in corruption, even when unauthorised information access or disclosure was not initially reported or suspected. An analysis of IBAC’s investigations across its jurisdiction in Victoria showed approximately 60 per cent of all investigations have included some form of information misuse, although this may not have been the original allegation investigated.

-

Information management for public sector agencies and their employees in Victoria is complex and can be difficult to navigate depending on the type and context of information held.

Victoria has a large legislative framework and governance around information management within the public sector. For local government, this framework includes, but is not limited to:

- standards for responsible management of information, as outlined in the PDP Act, from capture and creation of records all the way through to disposal

- standards of keeping records in the Public Records Act 1973

- right to privacy in the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 (the Charter).

Misuse of information by council employees may constitute an offence under one of these Acts. However, information misuse by council employees is not an offence under the Local Government Act 2020, although it is likely to be a breach of the council staff code of conduct and therefore may be subject to disciplinary action.

Of note, local government is not subject to the Public Administration Act 2004.

OVIC is an independent regulator with combined oversight of information access, information privacy, and data protection. OVIC administers the Victorian Protective Data Security Framework (VPDSF) and Victorian Protective Data Security Standards (VPDSS),12 which applies to the majority of agencies and bodies across the Victorian public sector. OVIC is also responsible for:

- monitoring and ensuring compliance with the Information Privacy Principles (IPPs), which set out minimum standards for how Victorian public sector bodies should handle personal information

- providing an alternative dispute resolution service for individual privacy complaints which may be referred to the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) for determination

- investigating, reviewing and auditing compliance with the VPDSS and IPPs.13

Information management arrangements in local government are similar to those of the broader public sector in Victoria. All local councils in Victoria must abide by the Public Records Office of Victoria (PROV) mandatory recordkeeping principles. The PROV is responsible for issuing information management standards, and assisting agencies to comply with the Public Records Act 1973.

Of note, while Part 4, section 84 (2)(a) of the PDP Act explicitly excludes councils, it is common for them to act as, or perform the functions of, a public entity. Given these arrangements, most councils will oversee and administer the information security obligations of these entities and their data. This includes if a council acts or performs the functions of another public entity, it needs to apply the VPDSF and VPDSS in relation to those functions. For example, a Committee of Management for Crown Land Reserves is deemed to be a public entity, and is required to fulfill all associated obligations for that a public entity, including those set out under Part 4 of the PDP Act. This is still the case even when the public entity is nested within a council. If a council is unable to segment the information of the public entity from its broader council information holdings, it must report to OVIC on its overall approach to protective data security. In some circumstances, this may mean that council adopts the VPDSS for its broader information holdings as best practice.

OVIC recommends local government adopt the VPDSS.14 However, councils are also required to take ‘reasonable steps’ to protect personal information from misuse, loss, unauthorised access, modification and disclosure under the Information Privacy Principles.

As well as the references to information misuse in the IBAC Act, the unauthorised access and disclosure of information is referred to in other legislation in Victoria. For example, the Crimes Act 1958 lists relevant summary offences under section 247G regarding unauthorised access to or modification of restricted data.

MISUSE OF CONFIDENTIAL INFORMATION BY COUNCILLORS UNDER THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT 2020

The Local Government Act 2020 (the Act) includes the definition and offences for the misuse of confidential information by councillors, while misuse of information by employees is likely to be covered by the other legislation outlined in section 2.1. These different legislative frameworks reflect the different role that councillors have in the sector compared to local government employees who are responsible for council administration and business.

Specific to councillors, Part 6 of the Act relates to councillor conduct. It defines confidential information as including, but not limited to, council business information, security information, legal privileged information, personal information, private commercial information, confidential council meeting information, internal arbitration information, as well as Councillor Conduct Panel confidential information. This definition is significantly broader than what was contained in the former Local Government Act 1989.

The definition of serious misconduct includes (among other things) a councillor releasing confidential information in contravention of section 125 of the Act. This definition also allows for the LGI to pursue unauthorised disclosures under section 123 of the Act relating to councillors’ misuse of position; however, to do this, a councillor must have disclosed information to gain, or attempt to gain, an advantage.

-

The analysis of IBAC’s complaints and notifications data found complainants often do not allege unauthorised access and release of information even if it enabled misconduct or corruption to occur. This highlights there is a significant underreporting of information misuse. Therefore, while allegations provide an insight into reporting, IBAC’s data is unlikely to reflect the actual level of information misuse occurring. Training and education of employees is needed to raise awareness around detecting, preventing and reporting information misuse.

However, a higher proportion of complaints received by the LGI do allege information misuse – particularly unauthorised disclosures – by councillors rather than employees. During consultation, it indicated approximately one-third of the allegations LGI receives regard information misuse. The higher reporting rate to LGI is due to it being the complaints agency for breaches of the Local Government Act 2020. It is also possible that the higher reporting rate to LGI is due to councillors being more motivated to make a complaint to LGI against other councillors which could sometimes benefit the complainant’s own political agenda.

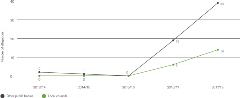

FIGURE 1 – ALLEGATIONS TO IBAC OF UNAUTHORISED INFORMATION ACCESS AND DISCLOSURE (1 JULY 2013 TO 30 JUNE 2018)*

*This graph does not include allegations against Victoria Police or its employees.

The allegations data in Figure 1 shows IBAC has received a very low number of allegations regarding information misuse against local government as well as other public sector agencies (excluding Victoria Police). Due to the low number of allegations, it is difficult to identify trends or patterns in the allegations.

IBAC assesses that local councils and the community often find it difficult to recognise information misuse and therefore report it as corrupt behaviour, especially when this behaviour has enabled other alleged offending such as bribery, fraud or collusion. Improved education on how information misuse may constitute corrupt conduct and enable further corruption, as well as how it impacts on citizens’ privacy, could strengthen reporting of information misuse.

Another reason why information misuse is underreported is that members of the public and public sector agencies, including local councils, are not aware of when their information has been misused or shared. For instance, unauthorised information access may not be detected, and unauthorised disclosures may not become public or reported back to the individuals or the agencies affected.

Additionally, these figures do not reflect the allegations of information misuse made to the LGI, which receives more allegations of information misuse due to it being the dedicated agency for complaints alleging breaches of the Local Government Act 2020.

-

The local government sector in Victoria includes 79 local councils, its employees, contractors and councillors. Councils across Victoria vary in geographical size, population and demography. While councils have great variability, each also has key responsibilities for planning, building, health services, waste management, emergency management, recreation and culture. Due to these responsibilities, local government manages a range of information which creates unique corruption risks.

Local council employees and councillors are both subject to codes of conduct mandated by the Local Government Act 2020. Due to provisions in this Act, the conduct required by councillors, particularly around not disclosing confidential information, is quite clear. While each individual council creates its own codes of conduct for councillors and employees, which potentially leads to different standards of ethics and integrity across the sector, this is mitigated by minimum standards for codes of conduct stipulated by the Local Government Act 2020 and its regulations.

IBAC conducted a corruption perception survey in 2017 and found local government employees have ‘a sound understanding of what corruption is and can distinguish between corruption and misconduct behaviours’.15 The survey identified that 15 per cent of respondents had observed misuse of information, 27 per cent of participants suspected misuse of information and 61 per cent of participants had the opportunity themselves to misuse information or material.16 In a list of overall risks, misuse of information was rated second only to conflicts of interest, ranking above all other categories, including the abuse of discretion and hiring friends or family for public service jobs.

-

Employees

Local government has significant land management, planning and zoning responsibilities which can directly affect property values. With property a common avenue for investing, there is a risk that local government employees could seek out and use official information on land or planning for personal financial gain. A 2017 survey of local government employees highlighted that 85 per cent of respondents perceived the use of official information in this way as corrupt, suggesting the local government sector is aware of some corruption risks related to information security.17

Under the Local Government Act 2020, local government employees must declare any conflicts of interest in line with their council’s policies and exclude themselves from any related activity, including any decision-making. However, based on allegations IBAC has received, managing these conflicts of interest remains a substantial issue for local government. IBAC intelligence also suggests there is an unknown number of conflicts of interests by employees in land and planning matters which are not declared and therefore cannot be managed. This indicates that employees may improperly benefit from using official information gained in their roles, especially if these interests were not previously declared and recorded.

While the Local Government Act 2020 provides a wider definition of what constitutes a conflict of interest compared to the previous legislation, at the time of this report it was not yet known exactly how these changes will impact on local government and employees’ awareness and reporting of conflicts of interest.

Councillors

Councillors are democratically elected by the community and are responsible for reviewing matters and issues before the council. They also set the overall direction for the municipality through long-term planning and decision-making, including land use planning and zoning matters. There is a risk of councillors accessing and disclosing information on these matters for direct or indirect personal financial benefit.

Information misuse is often easier to detect when it occurs for direct financial benefit. Like employees, under the Local Government Act 2020 councillors must disclose any conflicts of interest. Additionally, councillors must report personal interests to council biannually to ensure transparency in their decision-making, and mitigate against any unmanaged conflicts of interest.

IBAC analysis shows that where conflicts of interest are declared by councillors, they often relate to planning and construction matters. This is positive, as the financial and business arrangements of many developers can be complex and can therefore hide certain associations. Although it is encouraging that many councillors are declaring these types of conflicts, investigations by IBAC and interstate anti-corruption bodies highlight that some local councillors continue to use sophisticated strategies to hide conflicts of interest.18 This creates difficulties in detecting or investigating incidents of alleged corrupt conduct by councillors enabled by their access to official information and influence in council decision-making.

IBAC’s Operation Sandon is investigating allegations of serious misconduct, involving councillors from the City of Casey Council including allegations that they failed to disclose and/or manage conflicts of interest in relation to planning decisions. The potential conflicts being investigated by IBAC include conflicts arising from donations, and gifts and benefits.

IBAC’s investigations have also shown that misuse of land and planning information by councillors for indirect personal financial benefit is a growing area of risk. There have been incidences of councillors inappropriately disclosing information related to land and planning matters for the benefit of their associates. This subsequently strengthens their relationships and potentially encourages associates to return the favour at a later date. Another example of indirect financial benefit is where councillors disclose information to the media to influence community opinion on a matter before council which they could have a political interest in. Releasing this information could improve their chances of re-election or benefit their future career opportunities.

Accepting or soliciting a bribe for official information

Information misuse can occur when a local government employee or councillor accepts or solicits a bribe. When money or goods are exchanged for official government information, a financial advantage is created for both the recipient of the information and the person disclosing the information. Local government has a range of valuable information relating to planning or land rezoning, procurement, government grants and personal information of members of the community. This type of information may be of significant value to a motivated third party, and create an impetus for the offer of bribes or incentives.

As highlighted earlier, information misuse is often an enabler for other corrupt conduct to occur. Risk is heightened when local government interacts with the private sector leading to offers of inducements which may be viewed in the private sector as a normal cost of doing business. This type of behaviour can be difficult for local government and oversight bodies to detect as it often occurs through trusted connections.

Case Study 1 demonstrates how local government councillors might use their position to solicit money by sharing information on matters before council.

CASE STUDY 1 – MANDATORY NOTIFICATION TO IBAC PROFITING FROM INFLUENCING COUNCIL DECISION-MAKING

IBAC received a notification in May 2016 alleging a councillor had requested a kickback in return for their assistance in facilitating investment opportunities in Victoria for an overseas company. The councillor had requested a return of five to ten per cent of profits from the overseas company’s project for their assistance.

The complainant did not wish to provide further information or take the complaint further, and based on this, IBAC dismissed the matter. Notwithstanding, this case study demonstrates how councilors could use their positions and official local government information to benefit from mixed government and private industry projects.

CASE STUDY 2 – MANDATORY NOTIFICATION TO IBAC FALSIFYING QUOTES FOR WORK ALREADY APPROVED

In June 2017, IBAC received a mandatory notification from a metropolitan council under section 57 of the IBAC Act. The notification originated from a resident who alleged their employer, a contractor to local government, had requested the complainant make two quotes under two separate business names to submit to the council for works. The two quotes were for separate amounts with the quote under their employer’s business name for less than the other quote. The two quotes were submitted to a council employee in charge of procurement for the works. It was further alleged a councillor had already requested the complainant’s employer to undertake the work outside of proper procurement processes.

If substantiated, the allegations would constitute a breach of the council’s procurement policy and code of conduct for employees by the council employee in charge of the procurement, and a breach of the code of conduct by the councillor who had requested the work be undertaken. It may also constitute criminality by the contractor due to falsifying quotes. Based on the information submitted, the alleged corrupt conduct could be systemic within the area of the council responsible for managing this procurement. The conduct could also indicate that official information regarding local government procurement (including received quotes) was being leaked to preferred suppliers.

IBAC referred this notification back to the local council for investigation, noting that IBAC should be informed if serious corrupt conduct was detected.

This case study highlights how procurement processes can be manipulated through the unauthorised disclosure of official information.

-

Local government employees and councillors are at heightened risk of inadvertent information disclosures compared to other parts of IBAC’s jurisdiction due to the close proximity of their work to their local communities and often their friends and family. However, IBAC also receives allegations and information regarding deliberate information access and disclosure to benefit associates. Case Study 2 demonstrates how official information regarding local government procurement can be leaked to associates by both councillors and employees, negatively impacting the community through the improper use of public funds.

For councillors, inadvertent disclosures are often attributable to previous lack of experience working in the public sector, and the lack of training around information security and management of confidential information for councillors in some councils. This risk may be mitigated by the introduction of mandatory induction training for councillors under the Local Government Act 2020. This lack of experience may also mean that conflicts of interest are not identified and disclosed, making it easier to share information with associates without council oversight or a conflict of interest management plan to oversee the relationship.

IBAC consultations suggest local government employees and councillors have access to a wide range of official information – including while on leave and after business hours. This may be due to increased remote access local systems permitted in, and often necessary for, local government.

The VPDSS requires agencies to address risks presented by Victorian public sector employees who have remote access to information, including requiring organisations to establish, implement and maintain Information Communications Technology(ICT) security controls, which would include controls related to remote access.

It also requires organisations to embed information security continuity in their business continuity and disaster recovery processes and plans. This is relevant to most organisations that have business continuity plans which involve employees having remote access to public sector information.

It is the responsibility of each organisation to carry out a risk-based assessment and address the risk presented. Without these controls, employees can have easy access to information, often through information systems which have limited detection and auditing capabilities for unusual access patterns. With a lack of detection or oversight available for unauthorised information access, disclosure and use of this information is a heightened risk.

IBAC assesses the sharing of information with associates within the community and local media to be more of a consistent risk in rural and regional areas due to higher levels of interaction and the increased likelihood of conflicts of interest. Local government is a key employer across Victoria, with a higher proportion employed in regional and rural areas compared to other levels of government.19 Additionally, IBAC has been informed by stakeholders that smaller local councils often have limited resources to develop adequate anti-corruption capabilities and information security standards.

The type of information more at risk of being disclosed to associates varies across councils. For example, metropolitan councils, or those along Melbourne’s regional and metropolitan interface, more frequently have high-value projects, contracts and data holdings due to increased infrastructure, planning and development needs. Therefore, these councils are at higher risk of employees and councillors disclosing this type of information to associates due to the associated financial incentives.

-

Due to the different types of information routinely handled by public sector agencies, there are a range of corruption risks relative to their varied working environments. While there are shared risks across both the administration of local government and the elected representatives of council, the drivers of these risks for councillors are often markedly different due to the elected nature of their role. This is acknowledged in this section of the report where corruption drivers for councillors are analysed separately.

Public sector agencies, including local councils, are best placed to manage their own unique corruption drivers and risks.

Local councils, as with all public sector agencies, should regularly review and assess their information assets to determine how to appropriately protect the material. This would allow local councils to critically consider how to manage information based on their size, resources and risks. OVIC designed the Five Step Action Plan20 to assist agencies in this assessment.

-

As highlighted in Case Study 2, the unauthorised disclosure of information during procurement is a key corruption risk for local government. Financial management, including procurement processes, varies across local government, with the Local Government Act 2020 offering guidelines, rather than prescribed governance arrangements. The lack of uniform governance across individual councils may leave gaps in how procurement processes and information sharing are managed.

A procurement valued less than $10,000 is known as small value procurement, and has flexible policies which can often be interpreted to suit specific situations. This has been highlighted to IBAC as a key vulnerability for local government, as it means information management during procurement, including access and disclosure, may not be subject to the same levels of oversight as the rest of the public sector.21

Detailed procurement processes for local government would assist in preventing potential corrupt conduct, and help local government detect when anomalies occur. This could also offer a level of assurance for local councils which have a limited number of suppliers available for goods and services that are subject to procurement. To assist with this, Local Government Victoria issues Procurement Best Practice Guidelines to help councils understand their obligations under the Local Government Act 2020 and develop and maintain best-practice approaches to procurement.22 However, as stated above, these guidelines are not enforceable.

Case Study 3 on the next page highlights how the processes for procurement of goods and services can be corrupted through unauthorised access of information.

CASE STUDY 3 – IBAC’S OPERATION CONTINENT

DISCLOSURE OF PERSONAL LOG-IN DETAILS TO APPROVE PURCHASES

In 2013, IBAC started an investigation into a council works depot following a range of allegations including:

- a corrupt business relationship between a council employee and an external contractor

- false invoicing

- theft of council property including fuel, tools and vehicle parts by council employees

- the fraudulent purchase of goods by council employees.

While the allegation regarding fraudulent purchasing was substantiated, the other allegations could not be substantiated to IBAC’s satisfaction based on the evidence obtained. However, the investigation identified a number of issues in the conduct, management and supervision of the depot that had the potential to allow corrupt conduct to go unchecked. This included situations where an approver in the procurement process would often leave their computer log-in details and password on a Post-it Note on their computer so employees could approve purchase orders in their absence. This unauthorised disclosure of log-in details enabled corruption to take place.

The investigation led to a number of employees being dismissed by the council, and a number of other employees resigned.

-

Employees’ level of awareness of information security practices and how to share information with councillors varies greatly across the sector. Local government employees are responsible for the administration and business of the sector as well as the delivery of council services and functions. This includes providing advice and information to councillors as well as implementing any council decisions. However, local councils often have the difficult balancing act of ensuring that they are being both transparent to their communities (including via councillors) while also securing official information.

The LGI has previously noted a rise in complaints regarding the interactions between councillors and employees, and the misuse of council resources and expenses. It noted that many cases related to concerns that there were inadequate policies or guidelines in place to set standards for these interactions or that there were policies and guidelines but these were not consistently followed.23

In 2020, a city council was put into administration following an independent inquiry, which found a number of failings in governance and that the councillor group had become ineffective. While the inquiry noted many issues with how the councillors conducted their business, it also found that the processes for how employees provided information and advice to councillors had become problematic due to councillors not understanding or choosing ‘to ignore that their responsibilities did not encompass operational management and decision-making’. In some cases, councillors pressured and bullied employees if they did not get their way. The Chief Executive Officer (CEO) had introduced new protocols and procedures for how employees and councillors interacted, however councillors reported that these restricted and delayed the information provided.24

The PROV record-keeping principles and the Information Privacy Principles provide mandatory and minimum standards for local government’s information management. However, other recommended information security and privacy standards and initiatives (such as specialised privacy training, a privacy officer or the adoption of a privacy data security plan) are optional and often limited by the resources of specific councils. The lack of consistency in information management and security across the sector drives the risk that employees in councils with limited information management and security controls will access or disclose information without the proper authority. While this could occur unintentionally, it also limits the ability of employees to detect and report intentional improper unauthorised disclosures.

-

The Victorian Auditor-General’s Office (VAGO) conducted an audit of local government in 2015/16 and found information system controls were a key area of weakness across the sector. Some of the issues raised in the audit related to outdated security systems or updates, poor password policies, and the use of outdated and unsecure software. These weaknesses contribute to vulnerable information systems25 and processes which could then be misused by local government employees, councillors or external parties to obtain information without permission.

CASE STUDY 4 – UNAUTHORISED DISCLOSURE OF OFFICIAL INFORMATION BY A COUNCILLOR26

In August 2017, the Councillor Conduct Panel (the panel) found a councillor of East Gippsland Shire Council had ‘acted with serious misconduct’. This finding followed an investigation into allegations the councillor had released confidential information on the following occasions:

- between 8 December 2015 and 15 December 2015

- on 8 July 2016 to a television network

- between 10 May 2016 and 25 July 2016 to the Bairnsdale Advertiser.

While the panel found only the first and third allegation above could be substantiated, it found the councillor’s conduct in relation to the management of confidential information in the second allegation concerning.

The panel heard evidence that the councillor had been overheard admitting to releasing confidential information, arguing that they did ‘not hide anything from [their] constituents’. Furthermore, the councillor’s statements made it clear they were motivated by being transparent to the community. However, the panel stated the councillor failed to understand the requirements of relevant legislation.

The councillor was suspended for four months.

CASE STUDY 5 – LOCAL GOVERNMENT INSPECTORATE INVESTIGATION INTO UNAUTHORISED DISCLOSURE OF INFORMATION TO ADVANTAGE ANOTHER27

In September 2019, following an investigation by the LGI, a former councillor from South Gippsland Shire was proven to have made improper use of information acquired as a result of their position. The LGI found that, in January 2018, the councillor provided a resident of the municipality with information that they had acquired by virtue of their council position. The resident was involved in a legal proceeding against the council and the councillor provided emails and documents to assist or in an attempt to assist the resident in their proceedings.

While no conviction was recorded, the councillor was placed on a 12-month good behaviour bond and ordered to pay a $1500 contribution to a community organisation and $15,000 towards prosecution legal costs.

All South Gippsland Shire councillors were dismissed by the Victorian Government in June 2019.

THE ROLE OF COUNCILLORS AND DRIVERS OF INFORMATION MISUSE

Councillors are elected by their community for a four-year term to represent the interests of the community in the decision-making of council and contribute to its strategic direction. Councillors must consider the diversity of interests and needs of the municipal community when undertaking their role, and they agree to act lawfully and in accordance with the oath or affirmation of office and the standards of conduct. They must also comply with the council’s procedures required for good governance.

Importantly, the councillors also appoint the council’s CEO who is responsible for supporting the councillors and ensuring the effective and efficient management of the operations of the council. This includes being responsible for staffing the council and managing the interactions between employees and councillors.

The councillor role is inherently political due to it being a democratically elected role. Subsequently, there are some corruption drivers which are unique or more pronounced for councillors when compared to other public sector roles. These are detailed on the next two pages.

Sharing information with the community

Councillors face similar difficulties in balancing the need to be transparent with their constituents alongside managing confidential information as they are obligated to under the Local Government Act 2020.

Case Study 4 demonstrates the risks facing local government and councillors in managing official information while ensuring community interest are represented. It also demonstrates that in this instance, there was a lack of knowledge of the Local Government Act 198928 and the obligations the Act imposed upon councillors.

IBAC intelligence suggests there are other councillors who face difficulties in managing the balance between keeping information confidential and secure while also representing the community. These difficulties are more likely to arise for councillors, as opposed to local government employees, due to lower awareness of the legislation and requirements relating to information disclosure and decision-making protocols. This is especially the case for councillors recently elected.

Use of social media, particularly prior to elections

During consultation, the LGI noted it had experienced an increase in enquiries and complaints regarding social media following the 2016 local council elections. A high proportion related to online election material and campaign information.29

With the increasing use of technology and social media across society, the uptake by councillors or candidates in using social media to connect with the community is unsurprising and likely to continue due to its low cost and high accessibility. However, it can also provide a platform for unauthorised disclosures of official or confidential information (including by anonymous means) and for other misconduct during campaigns. This is a risk that will require ongoing management by local government, councillors and oversight bodies, such as the LGI and IBAC.

Political motivated disclosures

The work of councillors is inherently political due to the democratically elected nature of their roles. Additionally, it is becoming more common for candidates to be endorsed by political parties and for candidates to direct preferences during elections to those with similar views or ideologies, including on community matters.

Integrity agencies are more likely to receive allegations of information misuse by councillors than by other employees. The LGI reports approximately one-third of the complaints it receives relate to information misuse, with the majority of these being against councillors. One reason these allegations are more common is that other councillors may be motivated to report councillors they oppose.

Additionally, there is often a strong political motive for councillors to leak information on a matter before council to influence community or local media support for their position. In many cases, it is difficult to detect who disclosed the information due to the information being discussed at council meetings and known by all councillors.

Case study 5 shows how a former councillor made improper use of information to attempt to assist a resident in their proceedings against the council.

Management of the CEO

The councillors’ role in managing the CEO’s employment is a unique relationship, with the CEO responsible for supporting the mayor and implementing council decisions but also maintaining the integrity of local government.

An LGI investigation into an outer metropolitan council following an unauthorised disclosure to the media in December 2018 highlights the difficulties that can arise from this unique relationship. Confidential information about the termination clause in the CEO’s employment contract was disclosed with the local newspaper publishing the details. The LGI established that the information published was deemed confidential information under the Local Government Act 1989. It also established that of the 17 people aware of that information, 11 were councillors. However, due to three of the councillors having telephone contact with the local newspaper during the relevant time period, the LGI was not able to establish, beyond reasonable doubt, who disclosed the information.30

-

IBAC has identified a number of potential measures to assist in preventing unauthorised access and disclosure of information for consideration by local government, especially councils seeking to strengthen their information management frameworks.

This is not intended to be an exhaustive list and not all measures will be suitable for all councils. It is the responsibility of each council to implement corruption prevention strategies, and assess their own risks and operating environment to ensure the integrity and professional standing of their organisation.

Adoption of the VPDSF

As discussed on page 11, while Part 4 of the PDP Act explicitly excludes councils, it is common for them to act as, or perform the functions of, a public entity. Common examples of a public entity include Committees of Management for Crown Land Reserves, Cemetery Trusts or a body that is government controlled. Given these arrangements, most councils will oversee and administer the information security obligations of these entities and their data. This includes fulfilling the monitoring and assurance obligations of the public entities that they manage.

In addition, by implementing the VPDSS, councils would strengthen and standardise information security practices within their organisation, and in turn, contribute to better practices across the entire public sector.

Implementing reasonable security controls

OVIC advises that local government should adopt the VPDSF and its standards to assist in applying reasonable controls around information security. This includes, but is not limited to:

- establishing, implementing and maintaining a management regime for access to public sector data, including reasons for accessing the data and restrictions on access

- monitoring and updating security requirements in response to an evolving security risk environment

- information security training for employees (discussed on the next page)

- a proactive auditing program which is both a prevention and a detection strategy.

Further advice is available from OVIC.31

Reporting information security breaches, including suspected corrupt conduct

Organisations that are required to comply with the VPDSS must notify OVIC of incidents that have an adverse impact on the confidentiality, integrity or availability of public sector information with a business impact level (BIL) of 2 (limited) or higher. OVIC encourages local councils to contact OVIC in response to an information security incident. More information about reporting obligations and OVIC’s Incident Notification Form are available on OVIC’s website.

Where suspected corrupt conduct has occurred, this should also be reported to IBAC. Local council CEOs are required to report suspected corrupt conduct to IBAC under mandatory reporting obligations in section 57 of the IBAC Act. IBAC receives, on average, a higher rate of reporting from the local government sector compared to other areas within IBAC’s jurisdiction (excluding police). However, improvements can be made, especially in regards to reporting alleged misuse of information.

Increased reporting may also assist integrity agencies to identify trends and issues in information misuse as a way of providing improved and targeted prevention and detection strategies for local government.

Training, reporting and cultural change

Mandatory reporting by the public sector to IBAC of suspected corrupt conduct has been in place since December 2016. Since then, IBAC has received an increase in notifications from local government which suggests improvements in the general reporting of incidents. However, with information misuse incidents being significantly underreported across the entire public sector, improved awareness of how information misuse can constitute and enable corrupt conduct is needed. Increased reporting of breaches relating to privacy or information security would allow for increased information gathering between integrity agencies and local government to assist in improved education strategies for employees and councillors. This could inform improved policies and procedures to detect and prevent unauthorised access and disclosure of information.

Increased training in the legislative requirements for handling official and security-classified information could be of assistance to local government employees. The training resources provided by OVIC and PROV can complement the training already being delivered by local government or other bodies, such as the Municipal Association of Victoria and Local Government Victoria. This can be tailored to the needs of specific councils and complement other education programs to improve the understanding of data security among employees.

The legislative requirements for handling official and confidential information, and the associated corruption risks, should be incorporated into the training for candidates and councillors mandated by the Local Government Act 2020. This would improve awareness of information security and how it is fundamental to creating a culture of integrity.

-

Local government manages a wide range of residents’ personal and business information as well as council planning and business information. Protecting this official information is critical to the safety of the community, the use of public money in local government programs and services, and to maintain the community’s confidence in their local council. This information must be assessed and managed in accordance with its security value,32 and be based on business requirements, with adequate security measures in place to prevent and detect misuse, including unauthorised disclosures.

IBAC encourages the local government sector to consider the information in this report, and to review its information security accordingly, assessing how it may be vulnerable to misuse of information and related corrupt activities by employees and councillors. Raising the awareness across local government and the community that information misuse can enable – and also itself be considered corrupt conduct – will allow for improved prevention, detection and reporting of incidents when they do occur.

This report has analysed common risks of information misuse and the drivers of these risks across the local government sector. Similar risks are shared by public sector agencies across Victoria, providing opportunities to collaborate on best practices for information security.

The introduction of the VPDSF and VPDSS is a promising step forward as it provides local government with an opportunity to assess the information it holds and decide how best to secure it. The successful implementation of the VPDSS will result in improved information management and security practices, as well as an improved education of risks in these areas.

-

1 However, IBAC notes that the Public Administration Act 2004 does not apply to local government and its definition of the public sector does not include local government.

2 IBAC, Corruption risks associated with the corrections sector, November 2017.

3 IBAC, Special report concerning police oversight, August 2015.

4 Commissioner for Law Enforcement Data Security, Social Media and Law Enforcement, July 2013, p 44.

5 IBAC Act section 4(1)(d). Relevant offence means an indictable offence against an Act or the common law offences committed in Victoria for: attempt to pervert the course of justice; bribery of a public official; perverting the course of justice; or misconduct in public office.

6 Detrimental action refers to actions or incitements causing injury; intimidation; or adversely treating an individual in relation to their career in reprisal for making a disclosure or cooperating with an investigation in relation to a disclosure under the Public Interest Disclosure Act 2012.

7 Since the initial report, OVIC released Version 2 of the glossary in November 2019 – Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner, VPDSS Glossary V2.0, 2019.

8 SenateSHJ, Reputation Reality 2020: Getting ahead of the game - TransTasman perspectives on reputation and risk, March 2020.

9 IBAC conducted a survey of Victorian suppliers to state and local government in 2015–16, which found 38 per cent of respondents believed it was typical or very typical for public sector officials to give suppliers unequal access to tender information. IBAC, 2016, Perceptions of corruption: Survey of Victorian Government suppliers, p 2.

10 Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission, Organised Crime in Australia 2017, August 2017.

11 IBAC, Organised crime cultivation of public sector employees, September 2015.

12 The VPDSF is the overall scheme for managing protective data security risks in Victoria’s public sector.

13 Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner, Short guide to the Information Privacy Principles, 2018.

14 Office for the Victorian Information Commissioner, Local Councils and Privacy: Frequently Asked Questions, July 2017.

15 IBAC, Perceptions of corruption: Survey of Victorian local government employees, September 2017.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Queensland Crime and Corruption Commission, Operation Belcarra: A blueprint for integrity and addressing corruption risk in local government, October 2017.

19 Australian Centre of Excellence for Local Government, Profile of the Local Government Workforce, February 2015.

20 Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner, The Five Step Action Plan, July 2020.

21 Particularly the Departments and the specified entities subject to the policies of the Victorian Government Purchasing Board, which manages state purchase contracts. The policies include rules for public sector agencies to follow during procurement.

22 Local Government Victoria, Victorian Local Government Best Practice Procurement Guidelines 2013.

23 Local Government Inspectorate, Local government integrity matters – Spring 2018 <www.lgi.vic.gov.au/newsletters-bulletins>.

24 Blacher, Yehudi, Municipal Monitor’s Report on the Governance and Operations of the Whittlesea City Council, March 2020, pp 7-8.

25 Victorian Auditor-General’s Office, Local Government: 2015-16 Audit Snapshot, November 2016, p 6.

26 Local Government Victoria, Councillor Conduct Panel: In the matter of an Application by the Chief Municipal Inspector concerning Councillor Ben Buckley of East Gippsland Shire Council, 28 August 2017.

27 Local Government Inspectorate, Former South Gippsland councillor pleads guilty, 20 September 2019. Local Government Inspectorate, Local government integrity matters: Potential for damage from information leaks, 28 November 2019.

28 The Local Government Act 1989 was replaced by the Local Government Act 2020 in April 2020.

29 Local Government Inspectorate, Protecting integrity: 2016 council elections, April 2017 <www.lgi.vic.gov.au/council-investigations-and-audit-reports#2016-council-electionsreport>.

30 Local Government Inspectorate, Annual Report 2018-19, November 2019.

31 OVIC’s website is <www.ovic.vic.gov.au>, and further guidance material is available at <ovic.vic.gov.au/data-protection/standards/>.

32 The VPDSS defines security value as the highest overall business impact of the public sector information, based on a holistic assessment of compromise to confidentiality, integrity and/or availability. For more information, see OVIC, Practitioner Guide: Assessing the Security Value of Public Sector Information, Version 2.0, November 2019.