|

Acronym/term |

Explanation |

|

CMS |

Case Management System |

|

CPDP |

The Commissioner for Privacy and Data Protection. In 2017, amendments made to the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 merged the Offices of CPDP and the Freedom of Information Commissioner into the Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner. |

|

DHHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

DPC |

Department of Premier and Cabinet |

|

DTF |

Department of Treasury and Finance |

|

EPSO |

Ethical and Professional Standards Officer (Victoria Police) |

|

ISSC |

Victoria Police Information Systems and Security Command |

|

LEAP |

Law Enforcement Assistance Program |

|

NSW ICAC |

New South Wales Independent Commission Against Corruption |

|

IPP |

Information Privacy Principles |

|

IT |

Information Technology |

|

MoU |

Memorandum of Understanding |

|

Official information |

Any information (including personal information) obtained, generated, received or held by or for a Victorian public sector organisation for an official purpose or supporting official activities. This includes both hard and soft copy information, regardless of media or format. |

|

OPI |

The former Office of Police Integrity Victoria was the police oversight agency in Victoria from 2004 to 2013, after which time IBAC was established. |

|

OVIC |

Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner |

|

PROV |

Public Records Office Victoria |

|

PSC |

Victoria Police Professional Standards Command |

|

QLD CCC |

Queensland Crime and Corruption Commission |

|

ROCSID |

Victoria Police Register of Complaints and Serious Incidents Database |

|

SLEDS |

Standards for Law Enforcement Data Security |

|

UK |

United Kingdom |

|

Victoria Police employee |

All Victoria Police personnel and employees such as police officers, protective services officers, police recruits, police reservists and VPS employees |

|

VAGO |

Victorian Auditor-General’s Office |

|

VO |

Victorian Ombudsman |

|

VPDSF |

Victorian Protective Data Security Framework |

|

VPDSS |

Victorian Protective Data Security Standards |

|

VPS |

Victorian Public Service |

Research reports

Unauthorised access and disclosure of information held by Victoria Police

This report provides an overview of the key risks associated with unauthorised access and disclosure of information by Victoria Police employees. It explores the drivers of these risks, as well as potential prevention, reporting and detection measures.

The Victorian community rightly expects Victoria Police to protect and safeguard law enforcement data and official information it holds, and for employees to only use this information for a legitimate business need. When this data and information is accessed and disclosed without authorisation it compromises the safety of citizens and the community, and may constitute police misconduct or corruption. It can also enable further corruption and misconduct to occur.

This report focuses on Victoria Police and is one of three reports outlining the key risks of unauthorised access and disclosure of information within the public sector in Victoria. The other two reports focus on local government and state government bodies.

HTML version of the report

-

-

The Victorian community rightly expects Victoria Police to protect and safeguard law enforcement data and official information it holds, and for employees to only use this information for a legitimate business need. When this data and information is accessed and disclosed without authorisation it compromises the safety of citizens and the community, and may constitute police misconduct or corruption. It can also enable further corruption and misconduct to occur.

This report provides an overview of the key risks associated with unauthorised access and disclosure of information by Victoria Police employees. It explores the drivers of these risks, as well as potential prevention, reporting and detection measures. This report focuses on Victoria Police and is one of three reports outlining the key risks of unauthorised access and disclosure of information within the public sector in Victoria. The other two reports focus on local government and state government bodies.

Police perform an important role in protecting the community, often in difficult situations when people are at their most vulnerable. To assist police in this role, they are given significant powers and the community rightly expects them to use these powers honestly, responsibly and to perform their duties fairly, impartially and always in accordance with the law. As part of this expectation, the community expects information held by Victoria Police to be secure and used appropriately. The protection of law enforcement data and official information and the accountability of police to manage this appropriately is essential for community confidence in the police, and for the safety of police employees, members of the community and other organisations.

This report discusses how the misuse of information or material by public officers, acquired in the course of the performance of their duties, may constitute corrupt conduct.

Police rely on information from the public to help keep the community safe. Any incident or series of incidents which undermine public confidence in Victoria Police’s ability to secure official information and law enforcement data is likely to have flow-on effects on the willingness of the public to provide information that assists police.

The protection of information held by Victoria Police is important for all members of the community. Victoria Police holds law enforcement data and official information ranging from personal details of criminal involvement, to addresses and contact details, as well as intelligence on people considered a threat to the community. This information, which can be sensitive and requires protection, must be handled in line with best practice approaches to information security.

IBAC’s role includes informing the public sector and community about the risks and impacts of corruption, and ways it can be prevented. IBAC’s intelligence and research reports such as this report, help public sector agencies to identify corruption, and to expose and prevent it.

This report was informed by an analysis of IBAC findings from investigations and research, consultation with Victoria Police, interstate and Commonwealth integrity bodies, and agencies responsible for information security, information management and privacy in Victoria.

The unauthorised access and disclosure of information is a consistent theme of corruption investigations across Australia. IBAC’s previous strategic assessments and public reports have identified it remains a key issue in Victorian public sector agencies that hold classified or sensitive information, such as Corrections Victoria1 and Victoria Police2. Police, custody and correctional officers have access to law enforcement data and official information, including personal details of citizens, so it is unsurprising that a large proportion of investigations and assessments of alleged information misuse undertaken by IBAC and partner agencies focuses on these sectors.

Information held by Victoria Police can be misused intentionally and unintentionally. This unauthorised access and disclosure can lead to serious consequences for the people and organisations whose information has been misused, as well as Victoria Police and the public sector more broadly. These consequences can include:

- investigations being compromised

- the safety of victims or witnesses being threatened

- other organisations being less willing to share information with the police

- organised crime groups knowing how to avoid detection and plan further offending.

Increased technology use by the public sector and by the public has a significant impact upon how data is secured. The public sector has increasingly moved to storing information electronically, communicating via emails and other digital methods, capturing evidence via photographs, as well as using data analytics to inform how resources are used.

The increase in the use of technology for work and personal purposes has also increased the risk of public sector employees copying or replicating data for circulation. While electronic storage and exchange of information delivers productivity benefits for the work of the public sector, it has also made it ‘very easy to disclose information – in terms of time, quantity and sensitivity – and difficult, if not impossible, to retrieve it’3 once disclosed. It has also made it easier for Victoria Police employees to inappropriately use personal portable devices and mobile phones to save data to share with others, including on social media. This has previously been recognised by Victoria Police employees as the primary risk associated with social media.4

IBAC’s complaint data and intelligence suggest information misuse remains widely misunderstood by both police and the community. This leads to it not being detected or reported. The lack of identification or recognition of information misuse in turn makes it difficult for Victoria Police to manage this issue. More education is needed across the Victorian public sector, including Victoria Police, about how information misuse may constitute corrupt conduct, what the related corruption risks and potential impacts are, and available prevention and detection strategies.

1.1 Key findings

- Unauthorised access and disclosure of information are key enablers of other corrupt behaviour. These corruption risks are often overlooked as risks by agencies. This is evident in the lower than expected number of reports made to IBAC, and in the behaviours uncovered in investigations undertaken by IBAC and other public sector agencies. It is expected that as the understanding of information misuse as an enabler of corruption increases, this will help detection and investigation by Victoria Police.

- Unauthorised disclosures to the media is a risk across public sector agencies, including Victoria Police which frequently deals with issues of high public interest. These incidents are difficult to substantiate due to the source of the information leaks often being difficult to identify.

- Sharing information with approved third parties also presents many corruption risks. Although policies may be in place to control information access and disclosure by third parties, the proactive detection and enforcement of information misuse by agencies owning the information is difficult. This is especially relevant for Victoria Police, which holds significant private personal details about citizens.

- Increased use of personal devices and smart phones in the workplace has made unauthorised disclosure of information much easier. This is particularly the case for those Victoria Police employees who use their personal mobile phones to conduct their work duties,5 including using cameras to capture evidence or using applications to take notes or recordings.

- IBAC intelligence suggests information misuse is under-reported across the entire public sector, including Victoria Police. This may be due to it being under-detected, an under-appreciation for information security and privacy rights, or a lack of awareness that information misuse and disclosure may constitute an offence in itself.

- The number of reports of information misuse made to IBAC related to Victoria Police is higher than from other public sector agencies but is also declining. The higher number of reports may be due to Victoria Police employees and members of the public having a higher level of awareness of the risks related to information misuse, due to the large amount of sensitive information their organisation holds. The declining number of reports over time may reflect under-reporting and the difficulties in detection. A recent spike in reported incidents in 2017-18 may reflect improving information security practices by Victoria Police and its employees.

- Victoria Police and IBAC often do not detect information misuse until they are investigating other misconduct or corrupt actions. This is partly due to information security systems, which have not been fully developed, and a lack of proactive monitoring and auditing processes in place to detect unauthorised information access.

- Customised auditing of information access is under-utilised by Victoria Police and its benefits are under-appreciated. A program of proactive, extensive and repeated auditing could be used to identify and deter unauthorised access of information.

- The introduction in 2016 of the Victorian Protective Data Security Framework (VPDSF) and the Victorian Protective Data Security Standards (VPDSS) across the public sector is expected to reduce unauthorised information access and disclosure. For Victoria Police, the VPDSS does not represent a materially higher standard for information security than the previous Standards for Law Enforcement Data Security. However the VPDSS represents a shift from prescriptive standards to a more flexible risk-based approach.

1.2 Methodology

1.2.1 Scope

This report considers misconduct and corruption risks related to information misuse by Victoria Police and its employees.

IS THE UNAUTHORISED ACCESS AND DISCLOSURE OF INFORMATION CORRUPT?

The Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission Act 2011 (IBAC Act) defines corrupt conduct as (among other things) conduct of a public officer that involves the misuse of information or material acquired in the course of the performance of their functions, being conduct that would constitute a ‘relevant offence’.6

Unauthorised access and disclosure of information by Victoria Police employees can be considered corrupt conduct under the IBAC Act definition of corrupt conduct depending on the circumstances of access or disclosure.

Although unauthorised access of information driven by curiosity may not constitute corruption under the IBAC Act, it does constitute a form of police misconduct which is still relevant to IBAC’s jurisdiction and can bring the agency or the public sector into disrepute.

Unauthorised access of information is also considered an information security breach, and feeds into personnel security issues, of the individual not having a valid ‘need to know’, or having undergone an assessment to determine whether they are suitable or eligible.

The unauthorised access to, use of or disclosure of police information by Victoria Police employees is also an offence under sections 227 and 228 of the Victoria Police Act 2013.

Employees can make disclosures of information without the permission of their employer in the following circumstances.

Under the Protected Disclosure Act 2012, a person may make information disclosures to IBAC, an investigating entity or the public sector agency in question about employees of that entity if the information shows or tends to show the subject officer is engaging, has engaged, or is proposing to engage in improper conduct or detrimental action.7

All Victoria Police employees are subject to the Victoria Police Act 2013, which stipulates the confidential nature of police information. Specifically, sections 227 and 228 prohibit Victoria Police employees from accessing, using or disclosing police information without a reasonable excuse.

The Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner (OVIC) defines information management as the way in which an organisation plans, identifies, creates, receives, collects, organises, governs, secures, uses, controls, disseminates, exchanges, maintains, preserves, and disposes of its information.8 Good information management promotes good information security and assists in deterring unauthorised access and disclosure of information. This report also looks to other stages of the information management cycle where it is relevant to unauthorised access and disclosure of Victoria Police information.

Information misuse by private organisations or public sector employees of bodies outside Victoria is excluded from this report. However, case studies from other Australian policing agencies are highlighted to provide examples of key vulnerabilities and risks, which may be relevant to Victoria Police.

This report acknowledges that employees are allowed to disclose information without permission in certain circumstances, particularly when reporting police misconduct or corrupt conduct to IBAC, Victoria Police or another investigating entity. These types of disclosures (sometimes referred to as whistleblowing disclosures) are assessable for protections under the Protected Disclosure Act 2012.

1.2.2 Terminology

IBAC receives ‘complaints’ from the public and ‘notifications’ from public sector agencies about alleged corruption and police misconduct. A complaint or notification may include multiple allegations, which are assessed individually. This report includes summaries of allegations received by IBAC to illustrate some key points. IBAC notes there are limitations with the use of these examples, including:

- allegations are unsubstantiated at the time of receipt

- allegations can be incomplete, lack detail, from an anonymous source or may not individually name the subject of the allegation

- allegation data is not a comprehensive or reliable indicator of the actual prevalence of particular activities, or the risk mitigation practices and compliance activities already in place.

For further information on how IBAC assesses allegations, please visit our website.9

Despite these limitations, analysing allegations can help to identify trends or patterns and provide practical examples of these trends.

This report refers to a number of terms that are defined terms in the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014, including ‘personal information’, ‘sensitive information’ and ‘law enforcement data’. For clarity, these terms are used within the report in their ordinary sense, unless otherwise stated.

This report often refers to unauthorised access and disclosure of information as ‘misuse of information’.

-

The unauthorised access or disclosure of information held by public sector agencies can have wide-ranging and long-lasting adverse effects on the agency targeted, and on its employees. It can also affect the privacy and safety of citizens and therefore impact on community confidence in the security of information held by the public sector, as well as confidence more broadly in the public sector.

Accountability, trust and transparency in how public sector agencies protect and manage information, in particular sensitive information, is essential for good governance and the effective operation of the public sector. This is particularly the case for Victoria Police, which holds significant amounts of personal and sensitive information. Police also rely on information from the public to help keep the community safe. Any incident or series of incidents which undermine public confidence in Victoria Police’s ability to secure official information and law enforcement data is likely to have flow-on effects on the willingness of the public to provide information that assists police.

Information misuse can have negative financial consequences for the public sector. This includes information leaks to suppliers during procurement, which can lead to less competition in future procurement processes and consequent failure to deliver best value for taxpayers. Approximately one third of respondents to an IBAC survey of suppliers to state and local government in Victoria stated they were discouraged from tendering for work because of concerns about corruption.10 This reluctance may be influenced by a perception the tender has been awarded before the process has been completed. In 2017-18, Victoria Police spent approximately $14.04 million on consultancies, and entered into multi-year major contracts valued at more than $90.7 million.11 Given the significant value of procurements undertaken by Victoria Police, information misuse during the tender process would have serious financial consequences for the public sector and the community.

Information misuse can also assist organised crime and encourage further offending. The Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission has highlighted public sector corruption, including information misuse, as a key enabler for organised crime.12 IBAC has previously explored the issue of public sector employees providing information to organised crime entities.13 Victoria Police holds considerable information about organised crime groups and is tasked with the enforcement of legislation against these entities (with federal and state partners). Information leaks by Victoria Police employees to organised crime groups is serious and requires ongoing scrutiny, including continual auditing, training and guidance for employees.

IBAC’s investigations, particularly into police misconduct and corruption, have consistently identified information misuse as a key element in misconduct and corruption. This is the case even when unauthorised information access or disclosure was not initially reported or suspected. An analysis of IBAC’s investigations – a large majority of which are investigating alleged police misconduct or corruption – showed approximately 60 per cent of all investigations have identified information misuse, although this may not have been one of the original allegations made.

2.1 The legislative framework for information management in Victoria Police

Depending on the type of information held, information management for public sector agencies and their employees in Victoria is complex and can be difficult to navigate. This is especially the case for Victoria Police, which handles a wide range of information and has many information sharing arrangements with both Victorian, interstate and federal bodies.

All Victoria Police employees are subject to the Victoria Police Act 2013, which stipulates the confidential nature of police information. Specifically, sections 227 and 228 prohibit Victoria Police employees from accessing, using or disclosing police information without a reasonable excuse. Additional standards are set by guidelines and policies outlined in the Victoria Police Manual.

The Public Administration Act 2004 is also relevant for Victorian Public Service (VPS) employees of Victoria Police. This Act defines misconduct, among other things, as ‘an employee making improper use of information acquired by him or her by virtue of his or her position to gain personally or for anyone else financial or other benefits or to cause detriment to the public service or public sector’.

Victoria’s legislative framework and governance arrangements support information management within the public sector, including Victoria Police. This framework covers legislation, including, but not limited to, the:

- standards for responsible management of information in the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 from capture and creation of records all the way through to disposal

- standards of keeping records in the Public Records Act 1973

- right to privacy in the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006

- right to access documents held by Australian Government ministers and most agencies in the Freedom of Information Act 1982

- right to privacy of personal health information in the Health Records Act 2001.

OVIC is an independent regulator with combined oversight of information access, information privacy, and information security. OVIC administers the Victorian Protective Data Security Framework (VPDSF) and Victorian Protective Data Security Standards (VPDSS),14 which apply to the majority of agencies and bodies across the Victorian public sector. OVIC is also responsible for monitoring and ensuring compliance with the Information Privacy Principles (IPPs), which set out minimum standards for how Victorian public sector bodies must handle personal information. OVIC provides an alternative dispute resolution service for individual privacy complaints which may be referred to the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) for determination. OVIC also has powers to investigate, review and audit compliance with the VPDSS and IPPs.15 Other avenues for reporting misuse of information by Victoria Police include the Victoria Police Professional Standards Command (PSC) and IBAC.

Prior to October 2017, Victoria Police aligned its standards with part 5 of the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014, which specifically dealt with law enforcement data security and its standards. These standards were revoked in October 2017 and Victoria Police now operates under the VPDSF. There are also provisions for information management specific to certain types of information regulated under other legislation (eg Sex Offender Registration Act 2004, and the Health Records Act 2001).

The Public Record Office Victoria (PROV) is responsible for issuing the standards, and assisting agencies in achieving compliance, and for keeping records in line with the Public Records Act 1973.

Strong frameworks for the management of information, including governance, life cycle, business systems and processes, are essential to good information management processes;16 however, they may not fully prevent information misuse from occurring.

As well as the references to information misuse in the IBAC Act, unauthorised access or disclosure of information is referred to in other legislation in Victoria. For example, the Crimes Act 1958 lists relevant summary offences under section 247G regarding unauthorised access to or modification of restricted data, and section 82 of the Health Records Act 2001 specifies the offence of unlawfully requesting or obtaining access to health information.

2.2 Allegation trends

Analysis of IBAC’s complaints and notifications data found complainants often do not allege unauthorised access and release of information, even if it enabled misconduct or corruption to occur. This highlights that there is a significant under-reporting of information misuse. Therefore, while allegations provide an insight into reporting, IBAC’s data is unlikely to reflect the level of information misuse occurring. Training and education is needed to raise awareness around detecting, preventing and reporting information misuse.

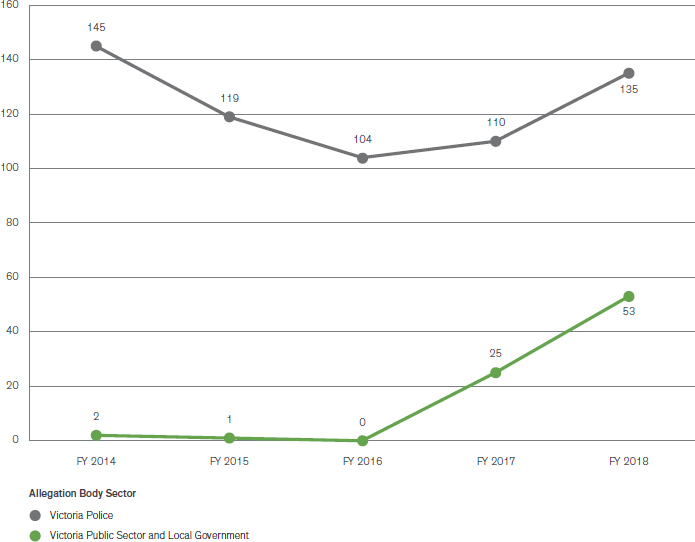

FIGURE 1 – ALLEGATIONS RECEIVED BY IBAC OF UNAUTHORISED INFORMATION ACCESS AND DISCLOSURE (1 JULY 2013 TO 30 JUNE 2018) Figure 1 shows a slight overall decline in allegations of information release and disclosures regarding Victoria Police over the past five years, however IBAC is unable to determine if this reflects an actual decline in incidents. A 2017 report by the then Commissioner for Privacy and Data Protection (CPDP)17 found that while there were some positive signs of progress regarding the level of Victoria Police organisational awareness of detecting and reporting information security incidents, organisational awareness remained lower than expected, and reporting of incidents was inconsistent and ineffective.18

Victoria Police has taken measures since the 2017 CPDP report to improve the security of police information as well as employee awareness of and attitudes towards information security. The increase in allegations in 2017-18 may reflect this work. As employees’ awareness of and attitudes towards information security improves, increases in reporting are expected.

IBAC receives a higher number of allegations of information misuse by Victoria Police employees than from the rest of the public sector combined. There are several potential contributing factors to this. Victoria Police makes a high number of mandatory notifications to IBAC regarding information misuse, indicating a strong information security framework that recognises when a breach occurs – resulting in more comprehensive complaints and notifications to IBAC. Other potential factors include:

- The public and Victoria Police are more aware of information misuse by Victoria Police following some high-profile cases and reporting by IBAC.

- There is more awareness within the community and Victoria Police of the large amount of official information of a personal, criminal and sensitive nature the agency holds.

- Other public sector bodies may not recognise the requirement to mandatorily report misuse of information as suspected corrupt conduct to IBAC.

-

3.1 Risks at the employee level

This section covers the common corruption risks IBAC has identified as associated with individual employees accessing and disclosing information without permission. This type of corrupt behaviour can be due to individual decisions and actions, as well as insufficient controls and systems, which are explored in section 3.2.

In 2015, IBAC produced a special report highlighting investigations conducted by IBAC and Victoria Police into instances of police unlawfully accessing and releasing information.19 While these cases were well publicised, the risks identified remain. Continual reinforcement of Victoria Police values and ongoing training are needed to ensure police information is only accessed and disclosed for authorised law enforcement purposes.

In a 2017 IBAC survey of Victoria Police employees, 87 per cent of respondents agreed there was opportunity for misuse of information to occur. This compares with 61 per cent of local government respondents and 56 per cent of state government respondents.20 This shows Victoria Police employees, while perhaps generally more aware of information security, perceive there are significant opportunities for employees to misuse this information.

3.1.1 Unauthorised access for personal interest

Victoria Police employees have access to a large volume of information on nearly all members of the public, including addresses, phone numbers, criminal histories and driver licence information. The scope and availability of this information raises the risk of it being accessed by Victoria Police employees for purposes unrelated to their police duties. There are multiple examples of police employees across Australia inappropriately accessing information on themselves, neighbours, friends and family, as well as high-profile individuals like sports stars and celebrities. Due to this, there are safeguards in place for Victoria Police information. For example, administrators of the Law Enforcement Assistance Program (LEAP) receive notifications when employees access someone with the same surname as them, or access the details of a person who is of interest to another Victoria Police unit.

Case Study 1 demonstrates an example of a police officer conducting unauthorised checks for their own self-interest.

CASE STUDY 1 – IBAC OPERATION CYGNET

THE USE OF VICTORIA POLICE RECORDS TO JUSTIFY INAPPROPRIATE RELATIONSHIPS

IBAC commenced an own motion investigation into allegations that a detective, working in a high-risk and sensitive area, may be using and/or trafficking drugs of dependence. While the investigation did not identify drug trafficking, it established the detective was a regular user of cannabis and cocaine.

Victoria Police employees are prohibited from using illegal substances. Illicit drug use exposes employees to the risk of compromise and corruption, for example by making them vulnerable to blackmail and coercion as well as impacts on their ability to perform their duties.

Operation Cygnet uncovered that the detective had regularly used Victoria Police systems to conduct checks on at least three associates who they received drugs from and used drugs with. When questioned by IBAC, the detective admitted to these unauthorised checks and stated that at least one of these checks was done because they wanted to ensure the supplier was not a ‘high-level drug dealer’, as the detective recognised that may jeopardise their position. The detective said the unauthorised checks they conducted on a second person were to ensure they were not associating with someone under investigation for drugs. Another reason for the check was to confirm if an associate had a criminal history in relation to drug use, or would constitute a declarable association to Victoria Police. The detective also admitted to conducting checks on their domestic partner to see what intelligence holdings existed.

Operation Cygnet did not find any evidence the detective had passed any information from their unauthorised checks to another person. Notwithstanding, it is likely the detective’s unauthorised checks influenced their continued association with drug users and suppliers, as the detective found no information suggesting these associates were high-level criminals. The unauthorised checks may have also influenced the detective’s decision to not declare an association with these people (as required under Victoria Police policy).

The detective resigned from Victoria Police while under investigation and faced no further disciplinary or criminal action.

LEAP is widely used throughout Victoria Police and is therefore the information system most likely to be unlawfully accessed for personal interest. LEAP is a database that holds the details of any individual who has had contact with police as a victim, witness or offender, and links directly into other databases such as the VicRoads Licensing and Registration Systems and the National Police Records Systems. Victoria Police’s management of LEAP and information governance has been subject to reviews by the former Office for Police Integrity (OPI),21 as well as OVIC’s predecessor agencies (the Commission for Law Enforcement Data Security and the Commission for Privacy and Data Protection) and other partner agencies.

While all LEAP users are required to agree to the terms and conditions of use upon login, recent IBAC investigations have found the terms to which users are agreeing are often completed as a ‘tick box’ rather than requiring employees to consciously engage with and acknowledge the privacy and legal implications of use. This may be due to the high frequency with which many police employees use LEAP and due to the system being designed this way for efficiency.

Queensland Police recently came under scrutiny for a spate of police officers misusing its law enforcement database (QPRIME). The Queensland Crime and Corruption Commission (QLD CCC) reported a five per cent increase in information misuse complaints for 2015/16. Between May 2016 and June 2017, at least five Queensland Police officers were charged with information misuse offences.22 Two of these are detailed in Case Study 2.

CASE STUDY 2 – EMPLOYEE CURIOSITY: ACCESS OF POLICE RECORDS TO VIEW HIGH-PROFILE MEMBERS OF THE PUBLIC

The Queensland Police Service (QPS) has had instances of unauthorised information access and disclosure, which have resulted in court action:

- In May 2017, a former Queensland Police Sergeant was fined $4000 (with no conviction) after pleading guilty to one charge of computer hacking. The police officer retired while under investigation for accessing QPRIME on 80 occasions between April and August 2016. It was stated he conducted checks on a wide range of people, including a prominent sportsperson, despite there being no legitimate law enforcement purpose to access the information.23

- In January 2017, a public figure launched civil action against the QPS after a right to information request discovered more than 300 officers had accessed their private information more than 1400 times. The public figure claimed the internal investigation by QPS was not sufficient and there was no reason for their identity to have been checked in the system so many times.24 The public figure previously received compensation from a case of false imprisonment against an officer who was allegedly stalking them.25

These examples highlight how high-profile members of the community may be more at risk of having their identities and personal details accessed unlawfully.

- In mid-2018, it was revealed that only seven of the 59 QPS officers investigated internally for unauthorised information access (referred to as a computer hacking offence under Queensland legislation) received disciplinary action during a 13-month period. In 52 cases, no further action was taken due to allegations being unable to be substantiated or deemed vexatious. The low number of allegations substantiated and resulting in discipline raised concerns that QPS does not have adequate measures in place to detect and investigate the unauthorised access of the personal details of citizens.26

The QLD CCC provides corruption prevention materials on corruption risks concerning access and use of confidential information, and instances of where corruption has occurred.27

In January 2017, the then Commissioner for Privacy and Data Protection noted Victoria Police had ‘fragmented documentation… for security incident management practices’ and a ‘limited visibility and definition of the link between security incidents and risks’.28 Such shortcomings could undermine Victoria Police’s systems for detecting unauthorised access of information. In light of the frequency with which unauthorised checks are identified in IBAC investigations of Victoria Police, it is highly likely the systems and audits in place are not sufficient to detect most unauthorised checks driven by personal interest.

Unauthorised access of LEAP may be detected by warning flags (also known as LEAP alerts) placed on specific entities (eg entities under investigation). If police employees are found to be checking an entity of interest to another business unit, the unit will follow up with the employee to find a reason for the check, and to gather any intelligence. This system relies upon business units to regulate other employees and to then report any suspicious checks to PSC. IBAC considers this system is of limited use as a deterrent to employees who wish to conduct unauthorised checks on associates, celebrities, high-profile citizens or current high-profile cases, as the use of warning flags is sporadic and usually limited to persons of interest in major investigations.

Victoria Police PSC conducts audits of LEAP on an ad hoc basis with basic algorithms to detect unauthorised access. These checks include if an employee looks themselves up, their address, or someone with the same surname. If the audit shows a positive match, a file will be created for assessment by PSC. IBAC’s view is that auditing of LEAP needs to be more robust, targeted, proactive and sustained.

3.1.2 Unauthorised information disclosure to media

The Leveson Inquiry29 in the United Kingdom (UK) highlighted the important role media play in shaping the relationship between police and the community. It found public confidence in the police is essential and noted the crucial role the media can play as a conduit for intelligence in relation to preventing and solving crime. However, it also noted there are risks associated with police and media relations, highlighting the relationship can be ‘fraught with difficulty’.30

Media assists Victoria Police to communicate with the community, including communications seeking witnesses to incidents, announcing community safety messages and appealing for information on police cases. However, when official information is made public, this can risk people’s safety, negatively affect investigations (for example, by alerting suspects and others to the current status of investigations), and discourage others from coming forward if they lack confidence in confidentiality and privacy protections. Unauthorised disclosures to media can also have a more damaging impact (compared to an unauthorised disclosure to one individual person) due to the fact that the information can be made instantly available to many people through broadcast, social media and online news services.

Unauthorised disclosure of information to the media is an area of increasing concern as more people use social media. Social media can make it easier to quickly disclose information without permission and presents challenges when investigating these disclosures. In particular, it is difficult to investigate and substantiate allegations of information disclosure when the information was disclosed in messages using encrypted technology.

In Victoria, section 126K of the Evidence Act 2008 protects journalists and their informants. This impacts the investigation of unauthorised disclosures of official information. The protection can complicate investigations making the allegations difficult to substantiate due to the source of information leaks often being difficult to identify.

Victoria Police has a policy framework for its employees regarding the release of information to the media, and instructs employees to liaise with the Victoria Police media unit prior to speaking to the media. It also outlines situations where official comment by Victoria Police is needed, and who is authorised to speak to the media. Policy also details the legislative provisions outlined earlier about unauthorised disclosure of information.

For this report, IBAC reviewed cases reported to IBAC and Victoria Police of unauthorised disclosures to media, and identified a range of motivations including:

- a disgruntled employee unhappy with the organisation or the direction of an investigation31

- a perception that privacy in the investigation is not warranted and the disclosure is in the best interests of the community due to the serious nature of the crime being investigated (eg homicides, assaults)

- a belief that providing more information to the public may encourage others to come forward.

Investigations in the UK have also identified journalists targeting police employees for access to police information.32 Although IBAC has not identified this in our investigations to date, strong prevention and detection controls around information security, and education around offering and accepting of inducements (including bribes or other benefits), can reduce these risks.

3.1.3 ‘Noble cause’ or politically motivated unauthorised information disclosures

Victoria Police officers regularly liaise with political and community groups. This liaison is essential to Victoria Police’s role to protect community safety and prevent crime. However, it can create risks of unauthorised disclosure of information to these groups as these relationships rely on frequent and current exchanges of information. Employees of public sector agencies, including Victoria Police, must be apolitical in their roles. Law enforcement systems contain valuable and/or sensitive data and information. Accessing and releasing information (including personal identifying information) for political purposes is a risk for Victoria Police, and this is highlighted in Case Study 3.

CASE STUDY 3 – RELEASE OF INFORMATION TO A POLITICAL CONTACT

In early 2018, Victoria Police notified IBAC that a Victoria Police officer had allegedly forwarded police information to a member of parliament in December 2017. The information was from an intelligence summary of events and incidents which had occurred that day and had the potential to affect Victoria Police operations. The police officer sent this information without any authorisation.

IBAC noted33 the allegations, forwarding them to Victoria Police to investigate.

The issue of unauthorised disclosures that are politically motivated has been highlighted to IBAC during consultations with the public sector, suggesting it is a risk across IBAC’s entire jurisdiction. For Victoria Police, high-profile criminal cases are particularly at risk, with IBAC receiving reports of unauthorised disclosures by Victoria Police employees to their friends, family members and the media.

There are also instances where disclosing information may be motivated by a ‘noble cause’ or what the individual considers ethical reasons. Case Study 4 illustrates that although these disclosures may be motivated by noble intentions, they may still be unlawful or in breach of policy (unless otherwise made under the Protection Disclosure Act 2012).

CASE STUDY 4 – DISCIPLINARY INTERFERENCE: DISCLOSURE ABOUT A WITNESS AND CAUTIONS TO A NEW EMPLOYER

In 2018, IBAC reviewed an investigation conducted by Victoria Police into the conduct of a senior employee. The senior employee was alleged to have directly interfered in a disciplinary inquiry by providing official information about a witness to a person who was involved in the inquiry. The senior employee had no authority to disclose this information.

Shortly after this, in a separate incident, the senior employee allegedly shared information with another agency that had recently recruited an ex-Victoria Police employee who had been dismissed following findings of misconduct related to the disciplinary inquiry. The senior employee, upon finding out the ex-employee had been employed at a new agency, informed the agency of the ex-employee’s disciplinary history.

Although the senior employee believed they were doing the right thing by informing the new agency of the risks of their new hire, the senior employee did not have the authority to do so. The senior employee should have redirected their concerns through their manager or to PSC to correctly identify if information should be shared with the other agency.

Victoria Police investigated the matter and subsequently terminated the senior employee’s contract.

3.1.4 Victoria Police employees targeted for information

Multiple IBAC investigations have shown repeated instances of Victoria Police employees unlawfully disclosing police information to associates. Often this information has been used for criminal purposes and financial benefit.

Victoria Police employees can be targeted due to their general access to law enforcement systems, not necessarily due to the unit where they work. This targeting can take place by friends and family, or by others known to them. Criminals can befriend employees with the aim of using them to access information (also known as grooming). Many Victoria Police employees have access to sensitive law enforcement data and official information, so it is difficult to detect employees who may be targeted and may offend.

An IBAC investigation, detailed in Case Study 5, demonstrates how unauthorised information access and disclosure remains a risk for police employees who may become complacent to the risk of being targeted or engaging in poor information security practices. Ongoing mandatory training is required by Victoria Police in the importance of information security.

CASE STUDY 5 – IBAC INVESTIGATION INTO CONDUCTING UNAUTHORISED CHECKS FOR FRIENDS

In 2018, IBAC concluded an investigation concerning a Victoria Police Detective Senior Constable who is alleged to have conducted LEAP checks and unlawfully disclosed this information to a friend.

The officer met the friend in the course of their duties and had later recommended the friend to be used as a source of information by a high-risk work area in Victoria Police. For at least three years, the officer conducted a number of checks for the friend in LEAP to ascertain the criminal history of the friend’s associates, and provided information about vehicles the friend had a commercial or personal interest in. The friend admitted to asking the officer to conduct checks for friends and family members.

The friend was then charged with serious criminal offences. The officer made no declarable association in relation to the friend as they were required to do by Victoria Police policy and continued the friendship.

The friend appeared to take advantage of the officer’s access to official police information. The officer, when questioned about the unauthorised checks, claimed it was part of their job as a detective to follow up claims of criminality brought to them by members of the community; however, this officer could not explain why they had not recorded information reports on the Victoria Police intelligence system, which is normal practice.

In May 2018, IBAC submitted a criminal brief of evidence against the police officer and at the time of the publication of this report, the matter is before the courts. The police officer was charged with offences relating to unauthorised disclosure, taking advantage of a regulated person’s position and possession of a prohibited weapon.

‘Reach back’ has been identified by integrity agencies as a common method for enabling criminal behaviour, including corruption. Reach back refers to when former employees seek out serving employees to provide favours, access or information.34 This has been observed in reports of alleged police misconduct and corruption as outlined in Case Study 6.

CASE STUDY 6 – ‘REACH BACK’ BY FORMER POLICE EMPLOYEES35

In September 2016, media reported on an investigation by Victoria Police’ Professional Standards Command (PSC). The investigation was about unauthorised access and disclosure of information following a police search of a nightclub for illegal drugs and large amounts of cash. Victoria Police information found to be linked to a local Criminal Investigations Unit was also located.

It was alleged the official information had been passed from a detective to a former police officer who was linked to the nightclub. The media also alleged one criminal figure was offering $1000 per check for police officers willing to leak information. This case highlights how police employees are at risk of being targeted by ex-colleagues and friends for information.

In 2017, a private investigator, who was also a former Victoria Police employee, was expected to be charged after seeking official police information from previous colleagues. This former police officer established a company with another former police officer, which specialised in investigating compensation fraud for major insurers and WorkCover.39 With many ex-police officers having transferable skills to the private investigations and security industries, and reports of former police establishing related businesses, there is an ongoing risk of Victoria Police employees being targeted for information by former colleagues.

The risk of private investigative companies seeking access to police information has been consistently highlighted across the last few decades, including in Victoria by the former OPI,36 the New South Wales Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC),37 and more recently in a review by New Zealand Police into the use of external security consultants.38

3.2 Risks at the organisational level

This section focuses on the common corruption risks IBAC has identified as associated with Victoria Police systems and processes for information security related to employees accessing and disclosing information without permission. This type of corrupt behaviour is often enabled by gaps or deficiencies in policies, systems and procedures.

3.2.1 Lack of detection of unauthorised access and disclosure

Victoria Police has had longstanding external scrutiny (currently by OVIC) of its information management arrangements, and this has led to an established risk management process. With the introduction of the VPDSF across the public sector, Victoria Police is sharing its experiences to assist other public sector entities to apply information management frameworks that better incorporate security and training.

Victoria Police has made few proactive detections of unauthorised disclosure of information, including to the media, political groups and other entities. Disclosure investigations can be resource-intensive and face challenges related to journalists being protected from revealing their sources as outlined in section 3.1.2. High-profile and sensitive matters are usually those which have a greater impact on the community due to the seriousness of offending, the level of harm the alleged offences have caused, or due to the role the people involved have in the community.

Noting that unauthorised disclosures of information may follow unauthorised access to police information systems, Victoria Police is advised to consider shifting its emphasis to consistent detection of the unauthorised access of information in sensitive and high-profile cases. This could include an ongoing audit program of information in these cases, which may also detect unauthorised disclosures, including those to organised crime figures.

Another risk for unauthorised access and disclosure of information is that there may be lower levels of information security practised by an employee after an employee submits their resignation but is still employed by Victoria Police. This is due to a perception by employees that there is both reduced detection and reduced consequences of information misuse during this time since they are soon to leave the organisation. Victoria Police advises IBAC it is introducing targeted auditing to address this risk.

To address these risks of unauthorised access and disclosure of information, IBAC recommends that the resourcing of Victoria Police’s information management security systems be further strengthened, including through an extensive proactive program of audits. Strengthening these systems would also assist Victoria Police’s ability to detect unauthorised access and disclosure of information by its employees.

3.2.2 Education and training

Victoria Police has around 21,000 full-time equivalent employees with approximately 3960 of these being Victorian public service (VPS) employees, including police custody service officers, forensic officers and VPS grade employees.40 A large number of VPS employees are lower level employees (VPS 2 and 3) in support roles, and often have the same access as police to law enforcement data and official information, including intelligence.

Victoria Police employees receive training on information management, including information security and appropriate use as part of their induction, either as recruits at the academy or via an induction program for non-police employees. Training is also delivered annually via an online learning module and in courses delivered for officers when they are promoted. However, the majority of Victoria Police employees stay at the same rank or at VPS level for a significant part of their career, meaning information management training is only delivered via online modules, or as part of other training. This means higher ranked employees are well trained in information management and employee obligations, but many lower level employees (who may access the data more often) are likely to have received formal training only once, at the beginning of their careers, and therefore have a lower understanding of the risks.

A 2015 report from the former Commission for Privacy and Data Protection stated Victoria Police employees recognise data security is a critical aspect of their jobs; however, they may still not be aware or mindful of the full range of risks. The report also found Victoria Police employees generally had the intent to comply with information security but the systems and resources of the organisation needed to improve the level of technical, preventative and educative support for employees.41

-

4.1 Personal issues of employees

The personal issues and circumstances of employees has been identified by both IBAC and integrity partner agencies as a key driver of intentional misuse of official information. Personal issues identified in IBAC investigations often relate to the overall health and wellbeing of the person alleged to have committed police misconduct or corruption, and this is often negatively impacted by alcohol and illicit drugs, breakdowns in personal relationships, gambling or periods of poor mental health.

Victoria Police has a range of employee assistance programs in place that assist with mitigating the risks of unauthorised access and disclosure of information driven by personal issues. It also has a Mental Health Strategy and Wellbeing Action Plan to strengthen these programs and encourage more people to seek help when needed. The plan notes how the stigma associated with mental health has previously dissuaded people from asking for help.

In 2016, Victoria Police published the Victoria Police Mental Health Review, an independent review into the mental health and wellbeing of Victoria Police employees.42 The review found that more people are using support services due to more services being offered and more help being accepted. This followed the 2015 Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission (VEOHRC) review to examine sex discrimination and sexual harassment in Victoria Police. While services set up in response to this are focused on sex discrimination and harassment, the traditional support services are available to address other personal issues. It is expected these programs and initiatives will lead to a decrease in information misuse driven by personal issues of employees.

CASE STUDY 7 – IBAC INVESTIGATION UNCOVERING LEAP USE FOR PERSONAL INTEREST

In early 2017, IBAC commenced an investigation into allegations that a Detective Leading Senior Constable was attending a metropolitan strip club and associating with the manager who was believed to be affiliated with an outlaw motorcycle gang.

The investigation sought to determine whether the officer had inappropriate relationships associated with the strip club, any criminal involvement or whether they were potentially compromised.

IBAC found that the officer had an ongoing association to the strip club dating back to at least 2011, and received favourable treatment in the form of free entry and free alcoholic drinks. This favourable treatment was not isolated to the officer, with the strip club having a business practice of giving free entry to Victoria Police employees (and other occupations or groups of people) and supplying them with complimentary drinks.

The investigation found the officer had substantial debts, including the balance of their 17-year-old mortgage being two and half times the amount the officer had purchased the residence for, and nearly $80,000 in credit card debt. This type of financial position puts a police employee at risk of compromise. The investigation also found the officer had withdrawn more than half their salary in cash near the strip club. The officer was frequently drinking alcohol to excess and admitted to IBAC they drove after consuming alcohol at the strip club.

On numerous occasions, the officer accessed LEAP for police information about their associates, some of whom they met at adult entertainment venues or through the sex work industry. On at least one occasion, the officer accessed and then disclosed police information to an employee of the strip club. On another occasion, the officer accessed and used police information for the apparent purpose of gaining the personal details of a sex worker who the officer had hired and lent money to.

The officer resigned from Victoria Police in early 2018 while under investigation. The officer subsequently also pleaded guilty to charges relating to the unauthorised access, use and disclosure of police information.

4.2 Social media use

Social media users, including police employees, may upload large amounts of personal information and opinions to both public and restricted social media platforms. Victoria Police recognises the risks social media use presents to its employees and the organisation and has a longstanding social media policy. However, it continues to face conduct issues related to social media, including the use of social media platforms to discuss work activity.

IBAC has identified that police employees – from recruits, to senior command, to ex-employees – regularly use Facebook and other messaging platforms to contact colleagues and discuss work activities. In cases where these messages may be password protected, Victoria Police employees may not appreciate the information they upload to these platforms as a risk or that the social media platform may now ‘own’ the information. This is likely to also increase the risk of official information being leaked by employees via social media and encrypted platforms without detection.

It is often difficult for law enforcement agencies to detect misuse of social media. This can be due to resourcing, privacy restrictions on social media accounts and difficulties in obtaining information via warrants when social media hosts are located internationally. Due to these difficulties, IBAC assesses that information disclosure on social media is often not detected and therefore under-reported.

To combat this, Victoria Police policy allows social media checks to be conducted upon potential recruits and employees; however, it does not proactively monitor social media to identify inappropriate information disclosures by its employees.

4.3 Information sharing with approved third parties

Victoria Police information is frequently shared with approved third parties. These include other law enforcement agencies across Australia and sometimes overseas, other Victorian public sector agencies and the federal government.

Under the VPDSF, agencies must have a level of assurance that approved third parties will offer the same, or better, protection of that information.43 Since the roll-out of the VPDSF, and the majority of public sector agencies having been required to adhere to the standards since June 2016, it is likely that secure information sharing practices across the Victorian public sector will have improved over the past few years. However, intelligence suggests that due to limited detection and auditing by Victoria Police, unauthorised information access and disclosure of Victoria Police data by third parties remains an issue for the organisation.

The ways in which these third parties use and store data that is accessed and received also affects the risk of Victoria Police information being misused. While the risks of third-party employees misusing information are similar to employees of Victoria Police, these risks are more difficult for Victoria Police to manage. The VPDSF’s stipulation that approved third parties must offer protection of this information acknowledges this issue and is designed to ensure the data used and stored by third parties is secured.

4.4 Information misuse under-prioritised in investigations

Victoria Police PSC is responsible for investigating suspected misconduct or corruption by Victoria Police employees. For suspected unauthorised access and disclosure of information, PSC investigations often rely on the Information Security and Standards Command (ISSC) to conduct audits of access. However, unauthorised access is often not the primary allegation being investigated, as seen by the low number of allegations of information misuse reported and notified to IBAC. This means that it is sometimes under-prioritised or not pursued in the investigation, with a high focus on the other alleged inappropriate conduct.

This low level of focus on unauthorised access and disclosure in investigations limits not only the full appreciation of the extent of issues, but consequently limits any resulting education or reform. Due to this, there is likely a gap for some employees connecting the importance of information security to integrity.

-

IBAC identifies a number of potential measures to assist in preventing unauthorised access of information and disclosure for consideration by Victoria Police and other public sector agencies seeking to strengthen their information management frameworks.

This is not intended to be an exhaustive list and not all the measures will be suitable for all areas of Victoria Police. Public sector agencies have primary responsibility for ensuring the integrity and professional standing of their organisations. Each agency is best placed to fully assess its own risks and operating environment, and to implement the best corruption prevention strategies to address risks.

5.1 Increased, targeted and sustained auditing program

When an auditing program is thorough, proactive and ongoing, it is considered an effective deterrent to employees considering conducting unauthorised checks. However, auditing of police information and data systems can be resource intensive.

A review of procedures for preventing and detecting information misuse, and strengthening of the auditing of systems would assist in a stronger implementation of the VPDSF across Victoria Police.

The majority of LEAP auditing by Victoria Police is considered to be reactive rather than proactive, and relies on reports of wrongdoing. While the LEAP system generates reports of some suspicious activity through warning flag alerts, the number of these alerts is low across the organisation and could be expanded. Additionally, some accountability has been shifted to intelligence practitioners to monitor these alerts. However, this does not address the underlying information security risk and also relies upon intelligence practitioners to act as auditors and question suspicious checks.

The former OPI, Victoria’s police oversight agency from 2004 until 2013, conducted a number of investigations into the use of LEAP, and in 2005 found that the auditing of LEAP was resource intensive and costly, with very few results of value (due to LEAP’s outdated framework); however, ‘a commitment to random and selective audits should be ingrained in [Victoria Police] philosophy’.44 This suggests that where auditing is difficult, a combination of prevention and detection strategies will be beneficial in increasing information security practices, and preventing information misuse.

An internally publicised targeted auditing program of high-profile cases, including those concerning celebrities and political figures, would help prevent and detect unauthorised accessing of information. Publicising audits would help contribute to building a culture within Victoria Police that believes that if you conduct unauthorised checks, you will be caught.

Victoria Police has advised it is now auditing employees’ access following resignation and separation to identify unauthorised access of information which may have occurred. This is partly in response to the perception that employees are less likely to follow proper information security once they know they are leaving Victoria Police. This prevention measure should help to detect unauthorised information access and disclosure by soon-to-be ex-employees and may deter current employees from similar acts.

5.2 Enhanced education and ongoing training

A key strategy for managing any corruption risks within an organisation is the implementation, maintenance and promotion of a sound ethical culture.45 While a strong, ethical culture is led from the leadership of an organisation, it is important for all employees to be involved in building this culture, including through ongoing communication and training about integrity and why it matters.

Victoria Police has training in place addressing information misuse and security. The PSC Ethical and Professional Standards Officer (EPSO) network across police regions delivers training materials, and the enhancement of this program may make employees more aware that information misuse may be corrupt conduct.

Most training takes places when an employee commences with the organisation and ongoing refresher training is limited, especially for employees who remain in the same position for a number of years. Ongoing training and awareness is essential, as the legislative, regulatory and administrative environments in which the Victoria Police policies operate regularly change.

Due to the complexity of the legislative framework and the VPDSF, clear communication and training is required for employees to be aware of their obligations. An increased focus on training in regional areas (which traditionally see employees stay for a longer time in positions) may increase information security awareness.

Police employees also need specific training on how to deal with the media and journalists in their professional roles and personal lives. This will help mitigate the risks of unauthorised disclosures to media. Basic training for all employees is encouraged to raise awareness around the seriousness and risks associated with leaks to the media. Raising awareness about the criminality of bribery and other inducements to provide police information should also be incorporated into this training.

While all Victoria Police (and public sector) employees must be apolitical and impartial in their roles, all employees have personal political views and their own personal understanding of ethics. When these views conflict with their roles as police employees, it is more likely that unauthorised disclosures of information will occur. Victoria Police’s conflict of interest policy and related training reinforces the need for employees to act with impartiality and to appropriately report and manage any actual, potential or perceived conflicts of interest.

Changing attitudes to ensure Victoria Police employees have a greater appreciation of the importance of information security is a key tactic for preventing unauthorised access and disclosure of information.46 Victoria Police has recognised this through its three-year cultural change program being undertaken across the organisation. This program has been enacted by the Victoria Police ISSC and has increased awareness and education alongside a new community of practice for information security. The challenge for Victoria Police is incorporating and allocating adequate time and focus to this topic in consideration of the large amounts of training that occurs within the organisation, as well as keeping its employees engaged on the topic so that they implement best practice.

Victoria Police has also initiated cultural change programs around mental health. These programs can help employees suffering from personal issues that are affecting their work to seek assistance. This may have a flow-on effect in terms of employees making better judgments in relation to information security.

-

The protection of official information and law enforcement data, including the personal information of Victorians, is critical to the safety of the community, and the community’s confidence in Victoria Police. This information must be secured and only accessed for legitimate authorised purposes, with adequate systems and training in place to prevent and detect misuse, including unauthorised disclosures.

Raising the awareness of public sector employees, including Victoria Police, and the community that information misuse can enable and also be corrupt conduct will allow for greater prevention, detection and reporting of incidents when they do occur.

This report analyses common information misuse risks and drivers of these risks across Victoria Police. The similar risks shared by other entities within the Victorian public sector create opportunities to learn and identify best practices for information security.

The introduction of the VPDSF is a promising step forward, giving Victoria Police and other public sector agencies the opportunity to assess the information they hold and decide how best to secure it. The successful implementation of the VPDSS is expected to result in better information management and security practices, and greater education about risks in these areas. With public sector agencies’ reporting obligations under the VPDSF to OVIC having commenced in August 2018, the more information that is included in reporting to OVIC, the more likely this will better identify information management risks and effective mitigations (including those related to corruption risks) for Victoria Police and other public sector agencies.

-

1 IBAC, Corruption risks associated with the corrections sector, November 2017.

2 IBAC, Special report concerning police oversight, August 2015.

3 Commissioner for Law Enforcement Data and Security, Social Media and Law Enforcement, 2013, p 44.

4 Ibid.

5 At the time this research was being undertaken, Victoria Police did not supply work mobile phones to the majority of its workforce. However, the BlueConnect Mobility Project was anticipated to deploy over 16,000 mobile devices by June 2019, in addition to the mobile devices already used by specialist areas and managers.

6 IBAC Act section 4(1) (d). Relevant offence means an indictable offence against an Act or the common law offences committed in Victoria for: attempt to pervert the course of justice; bribery of a public official; perverting the course of justice; or misconduct in public office.

7 Detrimental action refers to actions or incitements causing injury; intimidation; or adversely treating an individual in relation to their career in reprisal for making a disclosure or cooperating with an investigation in relation to a disclosure under the Protected Disclosure Act 2012.

8 Commissioner for Privacy and Data Protection, Glossary of Protective Data Security Terms, 2016.

9 What happens to your complaint?

10 IBAC conducted a survey of Victorian suppliers to state and local government in 2015-16, which found 38 per cent of respondents believed it was typical or very typical for public sector officials to give suppliers unequal access to tender information. IBAC, Perceptions of corruption: Survey of Victorian Government supplier, 2016, p 2.

11 Victoria Police, Annual Report 2017-18 Appendix H, October 2018, p 63.

12 Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission, Organised Crime in Australia 2017, 2017.

13 IBAC, Organised crime cultivation of public sector employees, September 2015.

14 The VPDSF is the overall scheme for managing protective data security risks in Victoria’s public sector. The former Standards for Law Enforcement Data Security (SLEDS), which stipulated standards for security and integrity of law enforcement data and crime statistics data systems, have been incorporated in the Victorian Protective Data Security Standards (VPDSS), which is part of the VPDSF. For more information, visit <www.ovic.vic.gov.au>

15 Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner, Short guide to the Information Privacy Principles, 2018.

16 Public Record Office Victoria, Recordkeeping for government: Getting started, 2017.

17 In 2017, amendments made to the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 merged the Offices of CPDP and the Freedom of Information Commissioner into the Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner.

18 Commissioner for Privacy and Data Protection, Review of the Victoria Police Security Incident Management Framework and Practices, January 2017, p14.

19 IBAC, Special report concerning police oversight, 2015.

20 IBAC, Perceptions of Corruption: Survey of Victoria Police employees, December 2017, p 7.

21 Office of the Police Integrity, Investigation into Victoria Police’s Management of the Law Enforcement Assistance Program, March 2005.

22 Coyne, Allie, IT News, ‘Another Qld cop charged with database snooping’. Published 13 June 2017.

23 Forbes, Thomas, ABC News, ‘Queensland sergeant fined for accessing police detail of netball captain Laura Geitz’. Published 3 May 2017.

24 Pierce, Jeremy, Courier Mail, ‘Former bikini model suing Queensland Police Service for $400,000’. Published 20 January 2017.

25 Bentley, Amelia, Brisbane Times, ‘Bikini model wins police pay-out after false imprisonment’. Published 16 September 2011.

26 Smee, Ben, The Guardian, ‘Queensland police computer hacking: no action taken in nearly 90% of cases’. Published 3 August 2018.

27 Crime and Corruption Commission, Corruption risks in access and use of confidential information, March 2018.

28 Commissioner for Privacy and Data Protection, Review of the Victoria Police Security Incident Management Framework and Practice, January 2017, p 12 and p 16.

29 The Leveson Inquiry was a public judiciary inquiry into the culture, practices and ethics of the press and its relationship to police and politicians. The report was published in 2012.

30 Davids, Cindy and Gordon Boyce, ‘Integrity, accountability and public trust: Issues raised by the unauthorised use of confidential police information’ in Accountability of policing by Stuart Lister and Michael Rowe (eds), 2016.

31 However, a disclosure relating to a public officer or public body engaging in improper conduct to an entity which may receive such disclosures under the Protected Disclosures Act 2012 is not an unauthorised disclosure, but a legitimate form of whistleblowing.

32 Miller, Joel, Police Corruption in England and Wales: An assessment of current evidence, United Kingdom Home Office Online Report 11/03, 2003.

33 ‘Noted’ is an outcome used by IBAC when notifications are received from Victoria Police under section 169 of the Victoria Police Act 2013. Unless IBAC determines to investigate the notification, these matters are retained by Victoria Police for action. IBAC ‘notes’ their receipt, and Victoria Police provides an outcome report at the completion of any action taken by Victoria Police. IBAC will then determine whether to review Victoria Police’s investigation.

34 Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity, Corruption Prevention Concepts: Grooming, June 2018.

35 McKenzie, Nick, John Sylvester and Richard Baker, The Age, ‘Nightclubs, dirty cops, drugs and leaks: the inside story’. Published 23 September 2016.

36 Office for Police Integrity, Past Patterns – Future Directions: Victoria Police and the problem of corruption and serious misconduct, accessed via IBAC’s website, February 2007, p.30.

37 Independent Commission Against Corruption (NSW), Report on unauthorised release of government information: Volume III, August 1992.

38 New Zealand Police, Outcome of Police investigation into the use of external security consultants, 18 December 2018.

39 Bucci, Nino, The Age, ‘The Melbourne private eye and the senior cop: Police leaks investigated’. Published 23 August 2017.

40 Victoria Police, Employees by Location at June 2019, July 2019..

41 Commissioner for Privacy and Data Protection, CPDP – Victoria Police: Wave 1& 2 – results (abridged), March 2015.