Risk and management

Half of the councils involved in the project have adopted risk assessment models that are integrated into budget and/or business planning processes.

While there are business management advantages of integration, corruption risks may not always be identified as impediments to achieving operational objectives. As such, it is important to ensure corruption risks are not forgotten in the process. Overall, councils are quite good at identifying and rating risks. However, councils could do more to implement and actively monitor the effectiveness of controls (eg. conducting audits and implementing recommendations).

Conflicts of interest: A large proportion of senior managers and staff at the councils involved in this project rated conflicts of interest as a medium- or high-risk issue, suggesting councils have a good awareness of the concept.

Procurement: Procurement-related issues were generally considered to be low-risk issues by both senior managers and staff. The risk was reduced to some extent by control mechanisms, such as minimising cash handling where possible, applying strict quotation and tendering procedures and aggregating the organisation’s spending.

Misuse of resources: A number of councils have used technology to minimise opportunities to access, copy and transfer information for illegitimate reasons. With assets, the greatest risks often relate to lower-value items – these are often more readily available and involve minimal oversight, making them easier to misuse without detection, albeit with less impact on a case-by-case basis.

Governance

Documented guidance: sound leadership, education and information for both staff and the public must complement each other in order to support the other risk management and detection elements of a council’s integrity framework.

Codes of conduct: Codes of conduct are a key mechanism used to govern council’s behavioural expectations of staff. The guidance in those codes could be reinforced with a statement of council’s intolerance for corruption and details of the penalties for breaching the code.

Leadership: CEOs varied in the balance of their approach to leadership, with some placing greater emphasis on values and organisational culture while others favoured the development and enforcement of controls. Neither culture nor controls should be pursued to the exclusion of the other.

Public information: At present the councils involved in this project are doing little to broadcast their intolerance of misconduct and corruption.

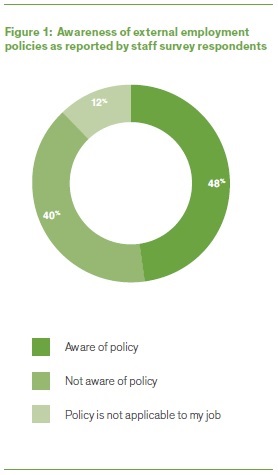

Staff education: A number of councils noted that continual education that reinforces formal training embed key messages within the fabric of the organisation. However, councils could do more to raise awareness of protected disclosure procedures and fraud and corruption policies, and requirements around reporting secondary employment.

Detection

Suspected corruption was most often detected by work colleagues, which highlights the importance of implementing clear and effective protected disclosure procedures and creating a safe reporting environment.

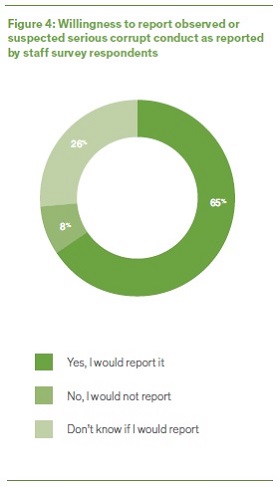

Reporting: In response to the staff survey, the majority of respondents (65 per cent) said they would report suspected corrupt conduct, however, eight per cent said they would not and the remaining 26 per cent said they did not know if they would report it.

Auditing: The role of audit committees has shifted from purely financial considerations to broader governance issues. All six councils had medium-term audit plans, some of which address corruption risks.