Key insights

- Organisations with high public interaction and visibility attract more allegations of corruption

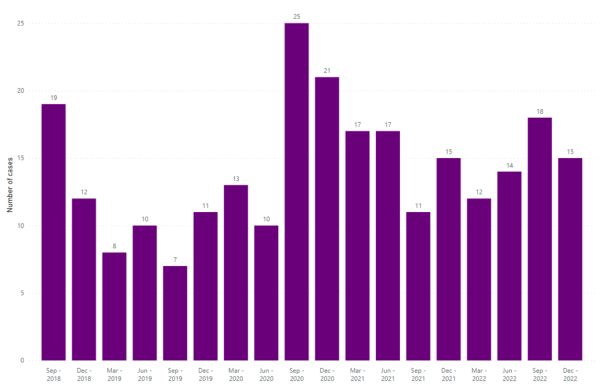

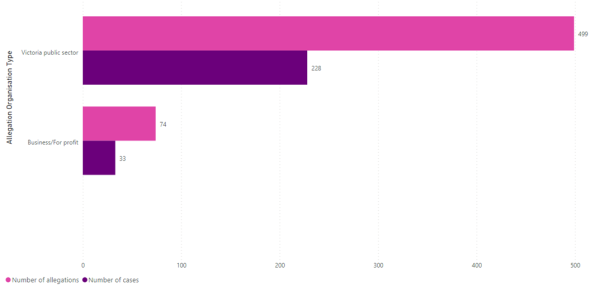

- Of the complaints and notifications received by IBAC relating to the transport sector from 1 July 2018 to 31 December 2022, 87% relate to public sector agencies or employees, not private sector contractors. This likely is due to the community being less aware that IBAC can investigate allegations against private sector contractors in some circumstances. Please note, this profile analyses complaints against the Department of Transport and Planning, its portfolio agencies and public transport services, but does not include allegations against the Major Transport Infrastructure Agency or the Suburban Rail Loop Authority.

Key corruption risks

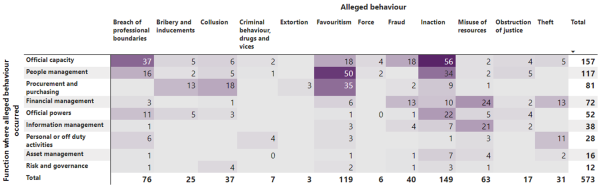

- Favouritism in people management and procurement practices

- recruitment or promotion of personnel without relevant experience, and the perceived or actual practice of cronyism

- departmental tender documentation being sent to a prospective tenderer in advance of its official release

- Inaction while acting in official capacities, such as through failing to take sufficient or appropriate action against fraudulent activity

- Poor identification and management of conflicts of interest, including in relation to personal acquaintances or family members

- Unauthorised access to and disclosure of sensitive personal and organisational information, which is then used to grant unfair advantage to a tenderer

- Collusion, including attempts to manipulate procurement and recruitment processes

- Fraud, including practices such as timesheet fraud, unauthorised use of funds, and false invoicing to reclaim expenses already paid

Key drivers of corruption risk

- Increased government spending in the sector

- Complex operating environments and processes, particularly in public-private partnerships

- High levels of dependence on a small pool of infrastructure contractors, which could lead to increased conflict of interest risks

- Lack of awareness about corruption and associated prevention and reporting strategies, particularly by contractors in transport and infrastructure delivery

- Increased pressure to deliver projects on time and within budget

High risk business areas

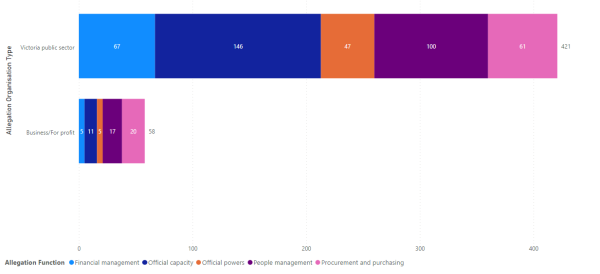

- Procurement, particularly for fraud or circumventing procurement processes

- Private sector transport contractors

- Collusion with contractors

- Misuse of information and other resources for personal/associate benefit

- Recruitment fraud

Key prevention and detection strategies

- Strong integrity frameworks that identify perceived, potential or actual conflicts of interest, as well as how they should be managed

- Proactive measures, such as mandatory and regular training and awareness raising to ensure staff – including private sector employees – are aware of and understand integrity-related policies and procedures

- Robust recruitment policies and procedures to ensure integrity from shortlisting, panel selection and vetting, through to induction

- Regular and random audits to ensure compliance with policies and procedures in risk areas such as procurement, recruitment and information security)

- Building a positive ‘speak up’ culture built on an integrity framework, and a leadership culture that leads by example

- Financial systems and technology that track activities related to procurement, contracts and purchases and detect anomalies

- Pleasingly, IBAC’s 2022 Perceptions of Corruption Survey of the Public Sector found that 37% of public sector employees who responded believe their organisation performs very well when it comes to ensuring strong policies, procedures and controls are in place. 40% considered it to be adequate.